Code

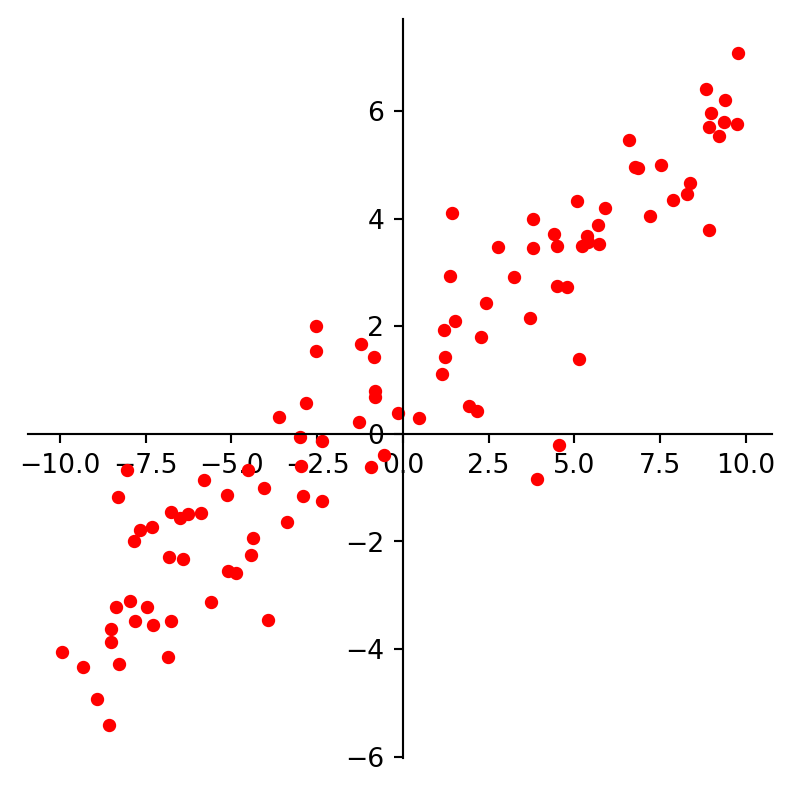

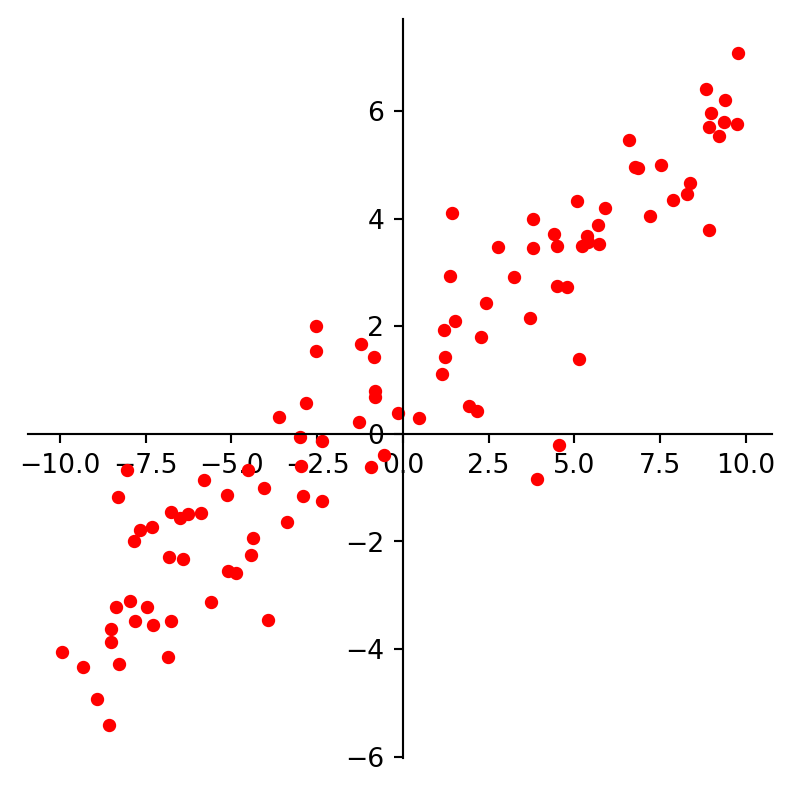

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

line = np.array([1, 0.5])

xlin = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

ylin = line[0] + (line[1] * xlin) + np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xlin, ylin, 'ro', markersize = 4)

plt.show()

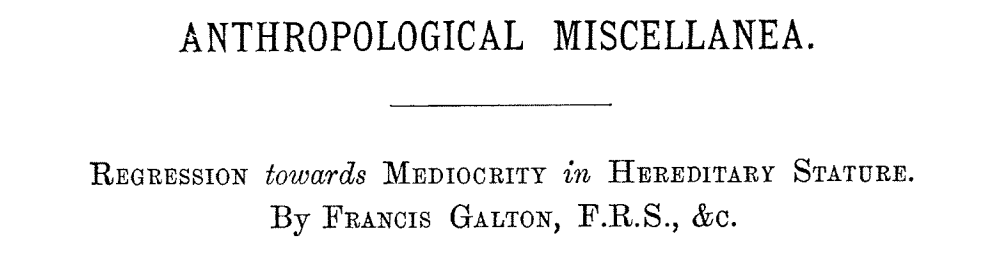

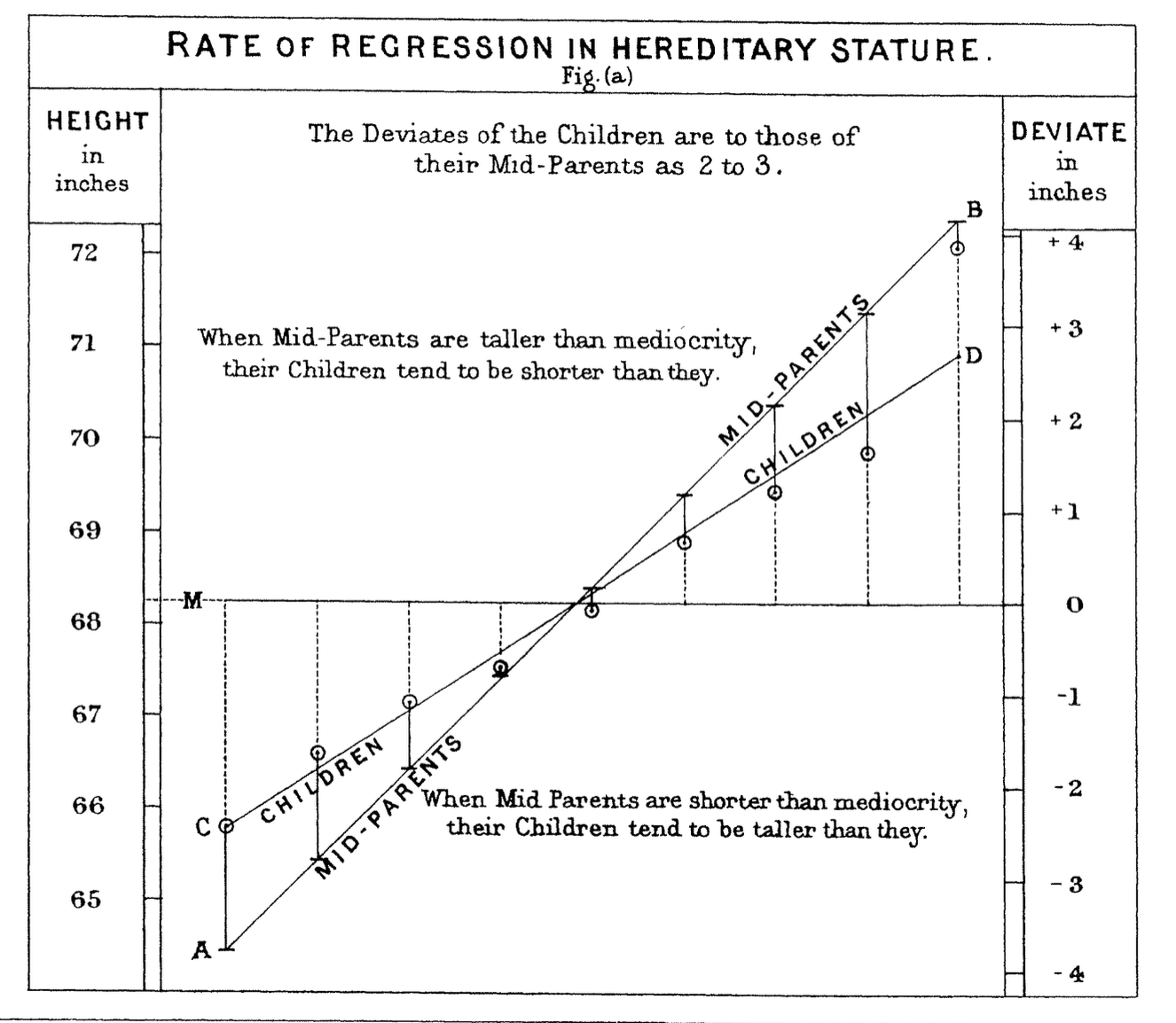

In 1886 Francis Galton published his observations about the height of children compared to their parents.

Defined mid-parent as the average of the heights of the parents.

When parents are taller or shorter than average, their children are more likely to be closer to the average height than their parents.

So called “regression to the mean.”

Galton fit a straight line to this effect, and the fitting of lines or curves to data has come to be called regression as well.

In the 60s, psychologist Daniel Kahneman studied the effect of praise versus punishment on performance of Israeli Air Force trainees. He was led to believe that praise was more effective than punishment.

Air force trainers disagreed and said that when they praised pilots that did well, they usually did worse the next time, and when they punished pilots that did poorly, they usually did better the next time.

What Khaneman later realised was that this phenomenon could be explained by the idea of regression to the mean.

If a pilot does worse than average on a task, they are more likely to do better the next time, and if they do better than average, they are more likely to do worse the next time.

Is it a good strategy to fire a coach after a bad season?

bad season -> fire and replace coach -> better season next year

When this could be interpreted as:

bad season (outlier) -> regression to the mean -> better season next year

“I had so many colds last year, and then I started herbal remedies, and I have much fewer colds this year.”

“My investments were doing quite bad last year, so switched investment managers, and now it is doing much better.”

When in fact, they could be (at least partially) explained by:

Regression to the mean

The most common form of machine learning is regression, which means constructing an equation that describes the relationships among variables.

It is a form of supervised learning:

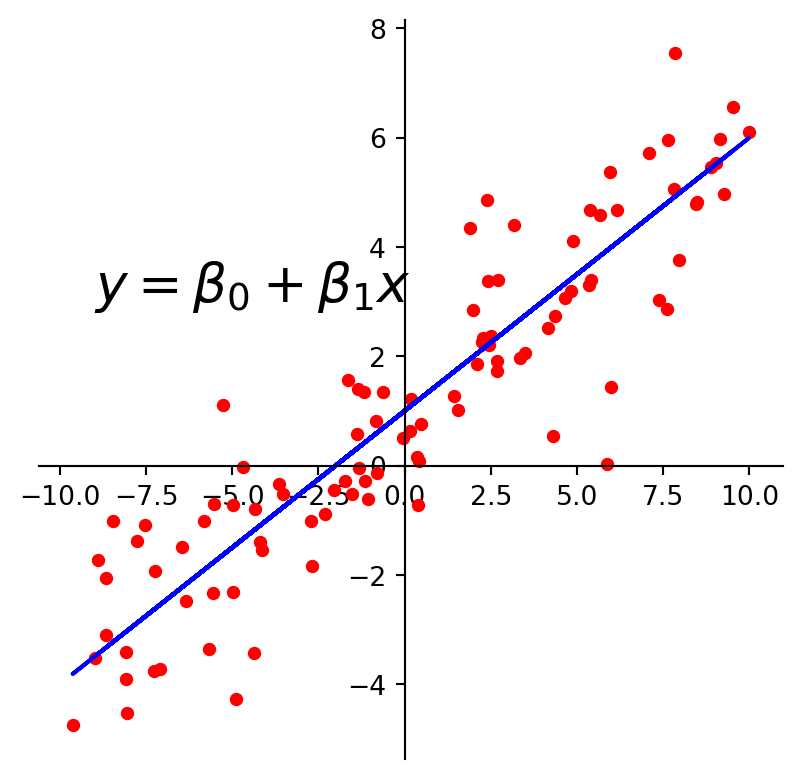

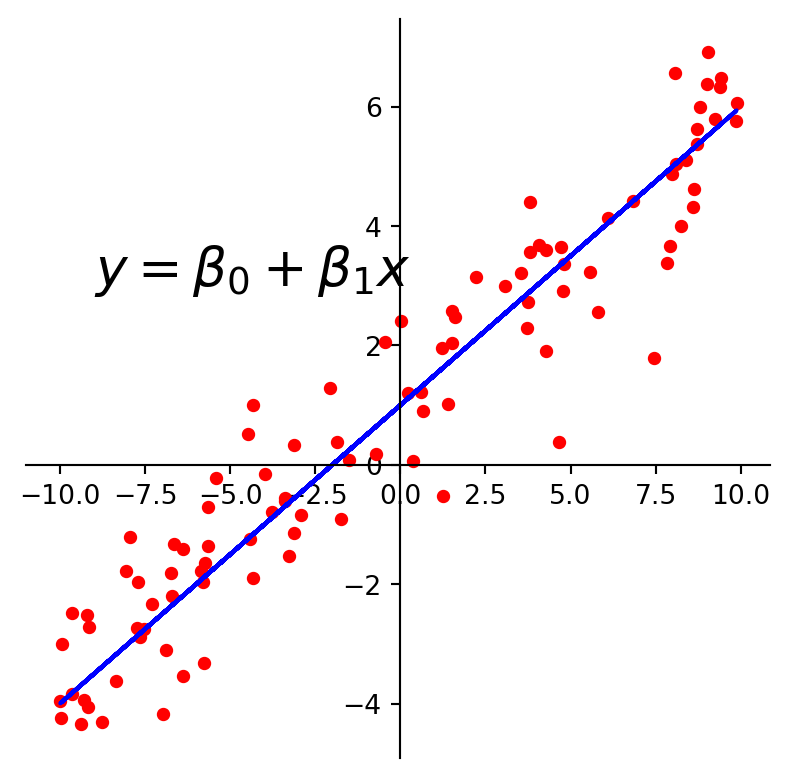

For example, we may look at these points and decide to model them using a line.

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

line = np.array([1, 0.5])

xlin = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

ylin = line[0] + (line[1] * xlin) + np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xlin, ylin, 'ro', markersize = 4)

plt.show()

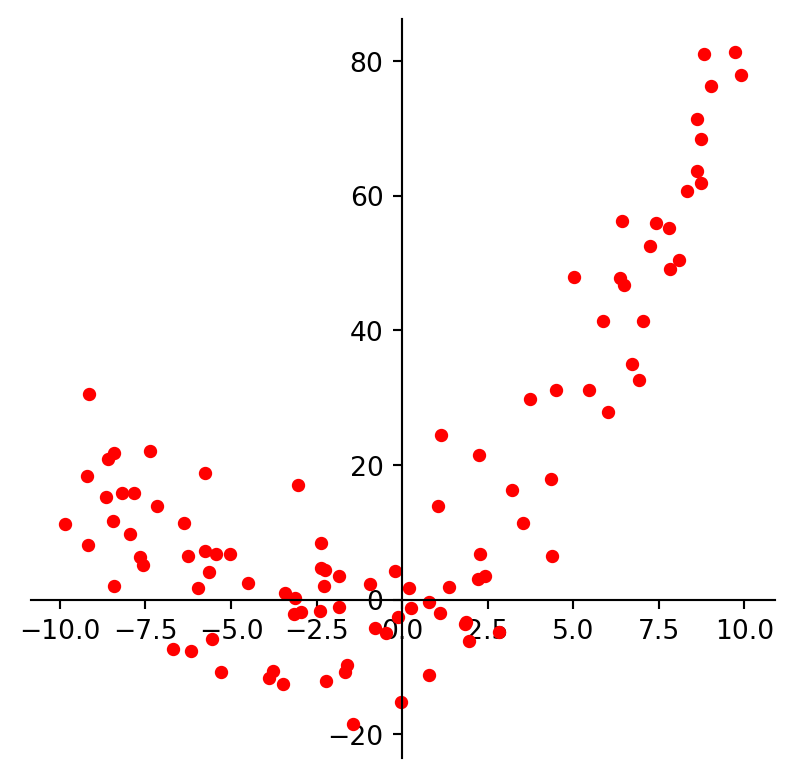

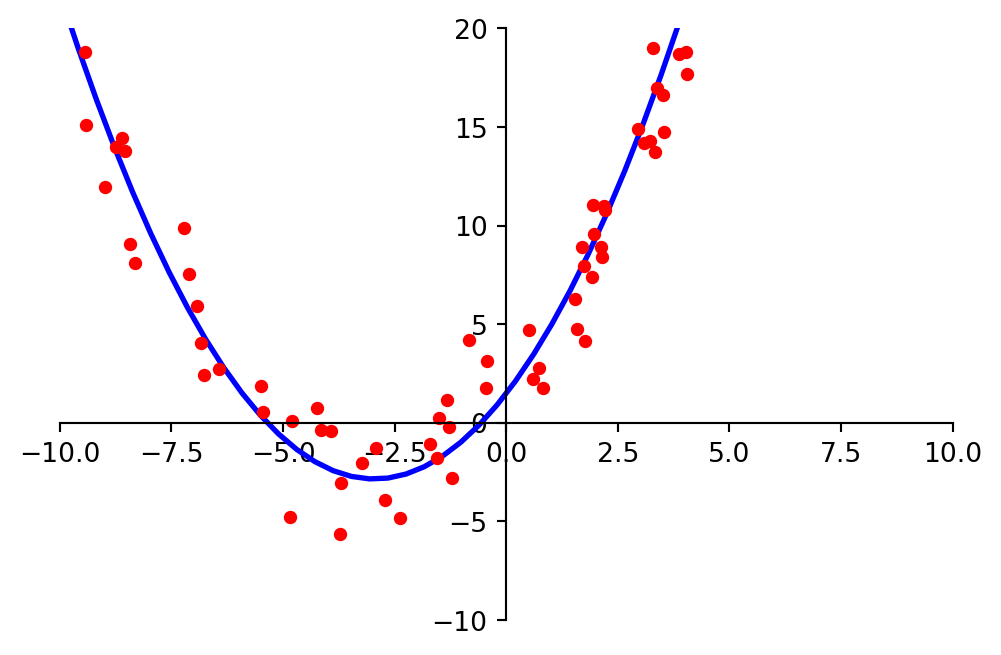

We may look at these points and decide to model them using a quadratic function.

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

quad = np.array([1, 3, 0.5])

std = 8.0

xquad = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

yquad = quad[0] + (quad[1] * xquad) + (quad[2] * xquad * xquad) + std * np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xquad, yquad, 'ro', markersize = 4)

plt.show()

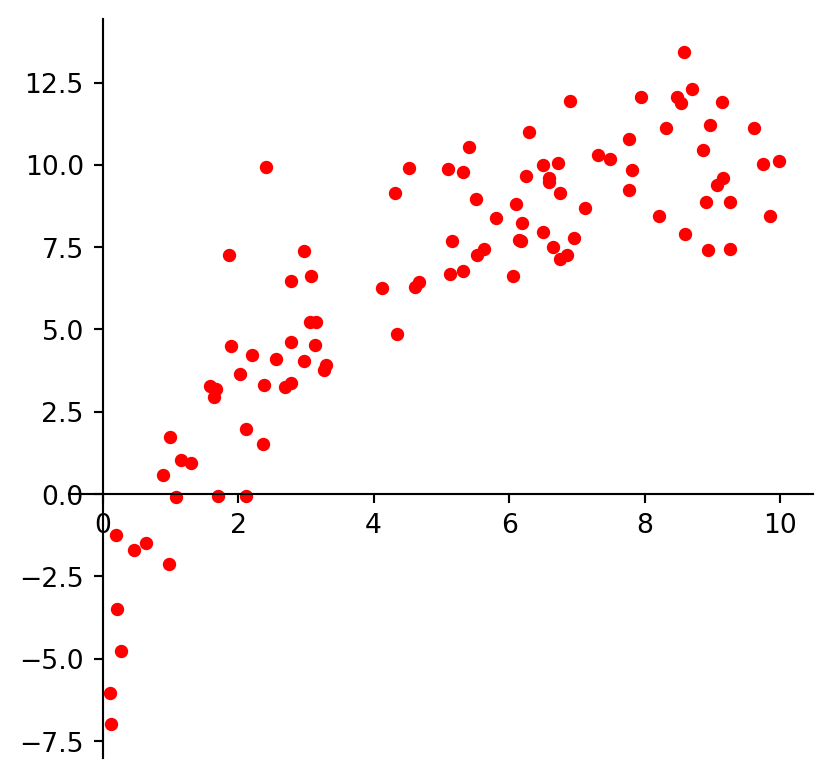

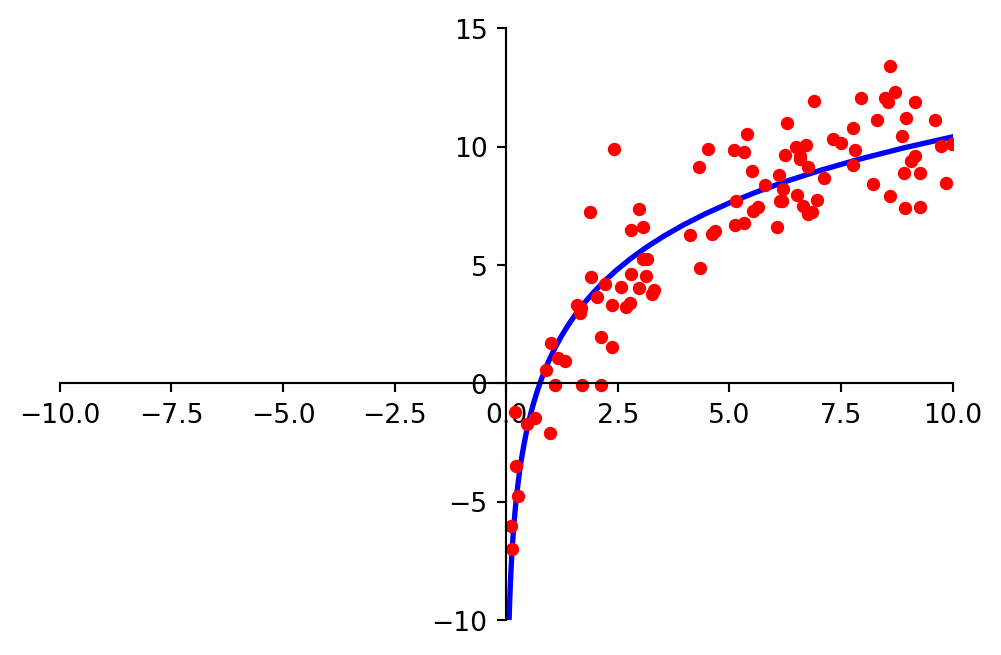

And we may look at these points and decide to model them using a logarithmic function.

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

log = np.array([1, 4])

std = 1.5

xlog = 10.0 * np.random.random(100)

ylog = log[0] + log[1] * np.log(xlog) + std * np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xlog, ylog, 'ro', markersize=4)

plt.show()

Clearly, none of these datasets agrees perfectly with the proposed model.

So the question arises:

How do we find the best linear function (or quadratic function, or logarithmic function) given the data?

This problem has been studied extensively in the field of statistics.

Certain terminology is used:

The basic regression task is:

The independent variables are collected into a matrix \(X,\) sometimes called the design matrix.

The dependent variables are collected into an observation vector \(\mathbf{y}.\)

The parameters of the model (for any kind of model) are collected into a parameter vector \(\mathbf{\beta}.\)

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

line = np.array([1, 0.5])

xlin = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

ylin = line[0] + (line[1] * xlin) + np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xlin, ylin, 'ro', markersize = 4)

ax.plot(xlin, line[0] + line[1] * xlin, 'b-')

plt.text(-9, 3, r'$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x$', size=20)

plt.show()

The first kind of model we’ll study is a linear equation, \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x.\)

Experimental data often produce points \((x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\) that seem to lie close to a line.

We want to determine the parameters \(\beta_0, \beta_1\) that define a line that is as “close” to the points as possible.

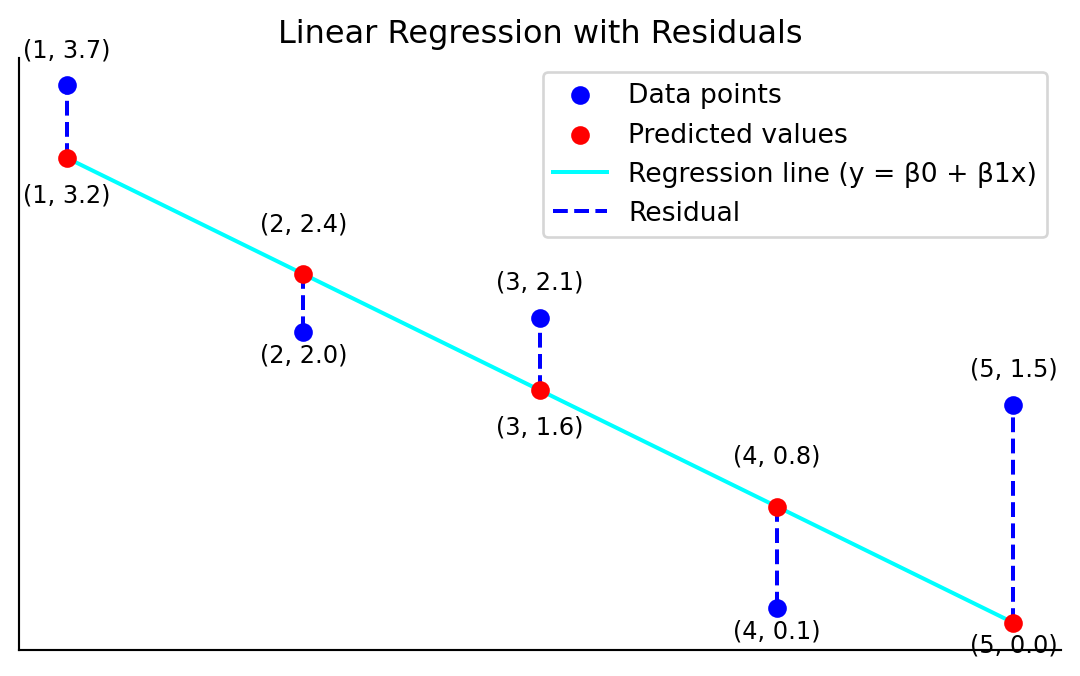

Suppose we have a line \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x\).

For each data point \((x_j, y_j),\) there is a point \((x_j, \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_j)\) that is the point on the line with the same \(x\)-coordinate.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Generate some data points

x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

y = np.array([3.7, 2.0, 2.1, 0.1, 1.5])

# Linear regression parameters (intercept and slope)

beta_0 = 4 # intercept

beta_1 = -0.8 # slope

# Regression line (y = beta_0 + beta_1 * x)

y_line = beta_0 + beta_1 * x

# Create the plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

fig.set_size_inches(7, 4)

# Plot the data points

ax.scatter(x, y, color='blue', label='Data points', zorder=5)

ax.scatter(x, y_line, color='red', label='Predicted values', zorder=5)

# Plot the regression line

ax.plot(x, y_line, color='cyan', label='Regression line (y = β0 + β1x)', zorder=4)

# Add residuals (vertical lines from points to regression line)

for i in range(len(x)):

ax.vlines(x[i], y_line[i], y[i], color='blue', linestyles='dashed', label='Residual' if i == 0 else "", zorder=2)

y_offset = [0.2, -0.2, 0.2, -0.2, 0.2]

y_line_offset = [-0.3, 0.3, -0.3, 0.3, -0.2]

# Annotate points

for i in range(len(x)):

ax.text(x[i], y[i] + y_offset[i], f'({x[i]}, {y[i]})', fontsize=9, ha='center')

ax.text(x[i], y_line[i] + y_line_offset[i], f'({x[i]}, {y_line[i]:.1f})', fontsize=9, ha='center')

# Remove the box around the plot and show only x and y axis with no tics and numbers

ax.spines['top'].set_color('none')

ax.spines['right'].set_color('none')

#ax.spines['left'].set_position('zero')

#ax.spines['bottom'].set_position('zero')

ax.xaxis.set_ticks([])

ax.yaxis.set_ticks([])

# Title

ax.set_title('Linear Regression with Residuals')

# Add legend

ax.legend()

# Show the plot

plt.show()

We call

The difference between an observed \(y\)-value and a predicted \(y\)-value is called a residual.

There are several ways to measure how “close” the line is to the data.

The usual choice is to sum the squares of the residuals.

The least-squares line is the line \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x\) that minimizes the sum of squares of the residuals.

The coefficients \(\beta_0, \beta_1\) of the line are called regression coefficients.

If the data points were on the line, the parameters \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) would satisfy the equations

\[ \begin{align*} \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 &= y_1, \\ \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_2 &= y_2, \\ \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_3 &= y_3, \\ &\vdots \\ \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_n &= y_n. \end{align*} \]

We can write this system as

\[ X\mathbf{\beta} = \mathbf{y}, \]

where

\[ X= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 \\ 1 & x_2 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_n \end{bmatrix}, \;\;\mathbf{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix}\beta_0\\\beta_1\end{bmatrix}, \;\;\mathbf{y}=\begin{bmatrix}y_1\\y_2\\\vdots\\y_n\end{bmatrix}. \]

Of course, if the data points don’t actually lie exactly on a line,

… then there are no parameters \(\beta_0, \beta_1\) for which the predicted \(y\)-values in \(X\mathbf{\beta}\) equal the observed \(y\)-values in \(\mathbf{y}\),

… and \(X\mathbf{\beta}=\mathbf{y}\) has no solution.

Now, since the data doesn’t fall exactly on a line, we have decided to seek the \(\beta\) that minimizes the sum of squared residuals, i.e.,

\[ \sum_i (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i - y_i)^2 =\Vert X\beta -\mathbf{y}\Vert^2. \]

This is key:

The sum of squares of the residuals is exactly the square of the distance between the vectors \(X\mathbf{\beta}\) and \(\mathbf{y}.\)

Computing the least-squares solution of \(X\beta = \mathbf{y}\) is equivalent to finding the \(\mathbf{\beta}\) that determines the least-squares line.

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

line = np.array([1, 0.5])

xlin = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

ylin = line[0] + (line[1] * xlin) + np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xlin, ylin, 'ro', markersize = 4)

ax.plot(xlin, line[0] + line[1] * xlin, 'b-')

plt.text(-9, 3, r'$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x$', size=20)

plt.show()

Now, to obtain the least-squares line, find the least-squares solution to \(X\mathbf{\beta} = \mathbf{y}.\)

From linear algebra we know that the least squares solution of \(X\mathbf{\beta} = \mathbf{y}\) is given by the solution of the normal equations:

\[ X^TX\mathbf{\beta} = X^T\mathbf{y}, \]

because \(X\mathbf{\beta} - \mathbf{y}\) is normal (e.g. orthogonal) to the column space of \(X.\)

We also know that the normal equations always have at least one solution.

And if \(X^TX\) is invertible, there is a unique solution that is given by:

\[ \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} = (X^TX)^{-1} X^T\mathbf{y}. \]

For \(X^T X\) to be invertible, where \(X\) is an \(n \times p\) matrix (n observations, p features):

Another way that the inconsistent (.i.e. no exact solution) linear system is often written is to collect all the residuals into a residual vector.

Then an exact equation is

\[ y = X\mathbf{\beta} + {\mathbf\epsilon}, \]

where \(\mathbf{\epsilon}\) is the residual vector.

Any equation of this form is referred to as a linear model.

In this formulation, the goal is to find the \(\beta\) so as to minimize the norm of \(\epsilon\), i.e., \(\Vert\epsilon\Vert.\)

In some cases, one would like to fit data points with something other than a straight line.

In cases like this, the matrix equation is still \(X\mathbf{\beta} = \mathbf{y}\), but the specific form of \(X\) changes from one problem to the next.

In model fitting, the parameters of the model are what is unknown.

A central question for us is whether the model is linear in its parameters.

For example, is this model linear in its parameters?

\[ y = \beta_0 e^{-\beta_1 x} \]

It is not linear in its parameters.

Is this model linear in its parameters?

\[ y = \beta_0 e^{-2 x} \]

It is linear in its parameters.

For a model that is linear in its parameters, an observation is a linear combination of (arbitrary) known functions.

In other words, a model that is linear in its parameters is

\[ y = \beta_0f_0(x) + \beta_1f_1(x) + \dots + \beta_nf_n(x) \]

where \(f_0, \dots, f_n\) are known functions and \(\beta_0,\dots,\beta_n\) are parameters.

Suppose data points \((x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\) appear to lie along some sort of parabola instead of a straight line.

ax = plt.figure(figsize = (5, 5)).add_subplot()

centerAxes(ax)

quad = np.array([1, 3, 0.5])

xquad = -10.0 + 20.0 * np.random.random(100)

yquad = quad[0] + (quad[1] * xquad) + (quad[2] * xquad * xquad) + 2*np.random.randn(100)

ax.plot(xquad, yquad, 'ro', markersize = 4)

plt.show()

As a result, we wish to approximate the data by an equation of the form

\[ y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2. \]

Let’s describe the linear model that produces a “least squares fit” of the data by the equation.

The ideal relationship is \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2.\)

Suppose the actual values of the parameters are \(\beta_0, \beta_1, \beta_2.\)

Then the coordinates of the first data point satisfy the equation

\[ y_1 = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_1 + \beta_2x_1^2 + \epsilon_1, \]

where \(\epsilon_1\) is the residual error between the observed value \(y_1\) and the predicted \(y\)-value.

Each data point determines a similar equation:

\[ \begin{align*} y_1 &= \beta_0 + \beta_1x_1 + \beta_2x_1^2 + \epsilon_1, \\ y_2 &= \beta_0 + \beta_1x_2 + \beta_2x_2^2 + \epsilon_2, \\ &\vdots \\ y_n &= \beta_0 + \beta_1x_n + \beta_2x_n^2 + \epsilon_n. \end{align*} \]

Clearly, this system can be written as \(\mathbf{y} = X\mathbf{\beta} + \mathbf{\epsilon}.\)

\[ \begin{bmatrix} y_1\\ y_2\\ \vdots\\ y_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}1&x_1&x_1^2\\ 1&x_2&x_2^2\\ \vdots&\vdots&\vdots\\ 1&x_n&x_n^2 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0\\\ \beta_1\\\ \beta_2 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \epsilon_1\\ \epsilon_2\\ \vdots\\ \epsilon_n \end{bmatrix} \]

Let’s solve for \(\beta.\)

m = np.shape(xquad)[0]

X = np.array([np.ones(m), xquad, xquad**2]).T

# Solve for beta

beta = np.linalg.inv(X.T @ X) @ X.T @ yquadAnd plot the results.

ax = ut.plotSetup(-10, 10, -10, 20)

ut.centerAxes(ax)

xplot = np.linspace(-10, 10, 50)

yestplot = beta[0] + beta[1] * xplot + beta[2] * xplot**2

ax.plot(xplot, yestplot, 'b-', lw=2)

ax.plot(xquad, yquad, 'ro', markersize=4)

plt.show()

Now let’s try a different model.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} y_1\\ y_2\\ \vdots\\ y_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}1&log(x_1)\\ 1&log(x_2)\\ \vdots&\vdots\\ 1&log(x_n) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0\\\ \beta_1 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \epsilon_1\\ \epsilon_2\\ \vdots\\ \epsilon_n \end{bmatrix} \]

m = np.shape(xlog)[0]

X = np.array([np.ones(m), np.log(xlog)]).T

# Solve for beta

beta = np.linalg.inv(X.T @ X) @ X.T @ ylogAnd plot the results.

#

# plot the results

#

ax = ut.plotSetup(-10,10,-10,15)

ut.centerAxes(ax)

xplot = np.logspace(np.log10(0.0001),1,100)

yestplot = beta[0]+beta[1]*np.log(xplot)

ax.plot(xplot,yestplot,'b-',lw=2)

ax.plot(xlog,ylog,'ro',markersize=4)

plt.show()

Suppose an experiment involves two independent variables – say, \(u\) and \(v\), – and one dependent variable, \(y\).

A simple equation for predicting \(y\) from \(u\) and \(v\) has the form

\[ y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 u + \beta_2 v. \]

Since there is more than one independent variable, this is called multiple regression.

A more general prediction equation might have the form

\[ y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 u + \beta_2 v + \beta_3u^2 + \beta_4 uv + \beta_5 v^2. \]

A least squares fit to equations like this is called a trend surface.

In general, a linear model will arise whenever \(y\) is to be predicted by an equation of the form

\[ y = \beta_0f_0(u,v) + \beta_1f_1(u,v) + \cdots + \beta_nf_n(u,v), \]

with \(f_0,\dots,f_n\) any sort of known functions and \(\beta_0,...,\beta_n\) unknown weights.

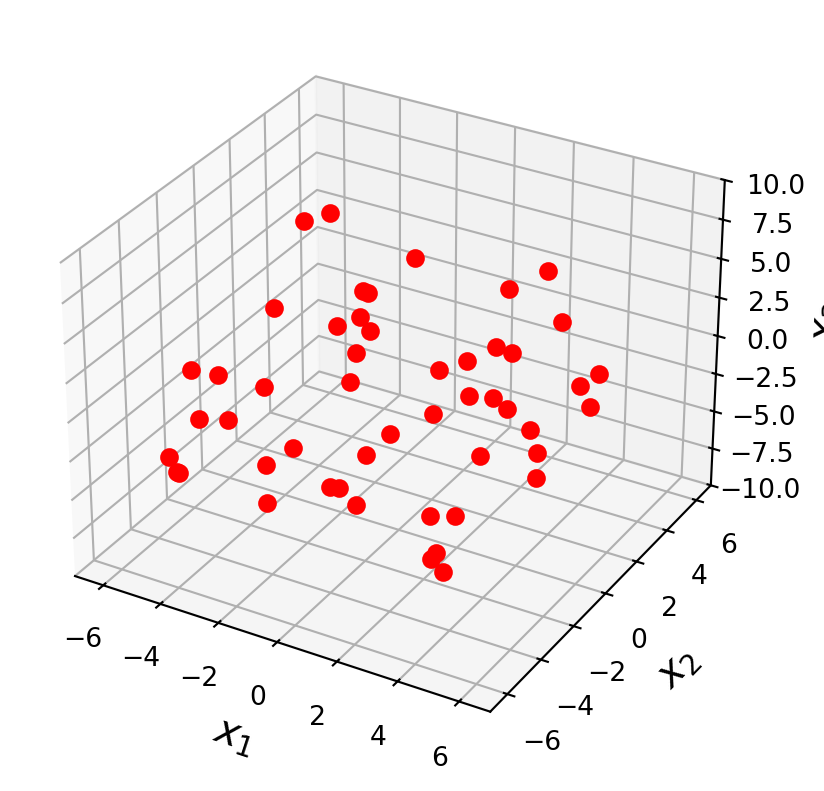

Let’s take an example. Here are a set of points in \(\mathbb{R}^3\):

ax = ut.plotSetup3d(-7, 7, -7, 7, -10, 10, figsize = (5, 5))

v = [4.0, 4.0, 2.0]

u = [-4.0, 3.0, 1.0]

npts = 50

# set locations of points that fall within x,y

xc = -7.0 + 14.0 * np.random.random(npts)

yc = -7.0 + 14.0 * np.random.random(npts)

A = np.array([u,v]).T

# project these points onto the plane

P = A @ np.linalg.inv(A.T @ A) @ A.T

coords = P @ np.array([xc, yc, np.zeros(npts)])

coords[2] += np.random.randn(npts)

ax.plot(coords[0], coords[1], 'ro', zs=coords[2], markersize = 6)

plt.show()

In geography, local models of terrain are constructed from data

\[ (u_1, v_1, z_1), \dots, (u_n, v_n, z_n), \]

where \(u_j, v_j\), and \(z_j\) are latitude, longitude, and altitude, respectively.

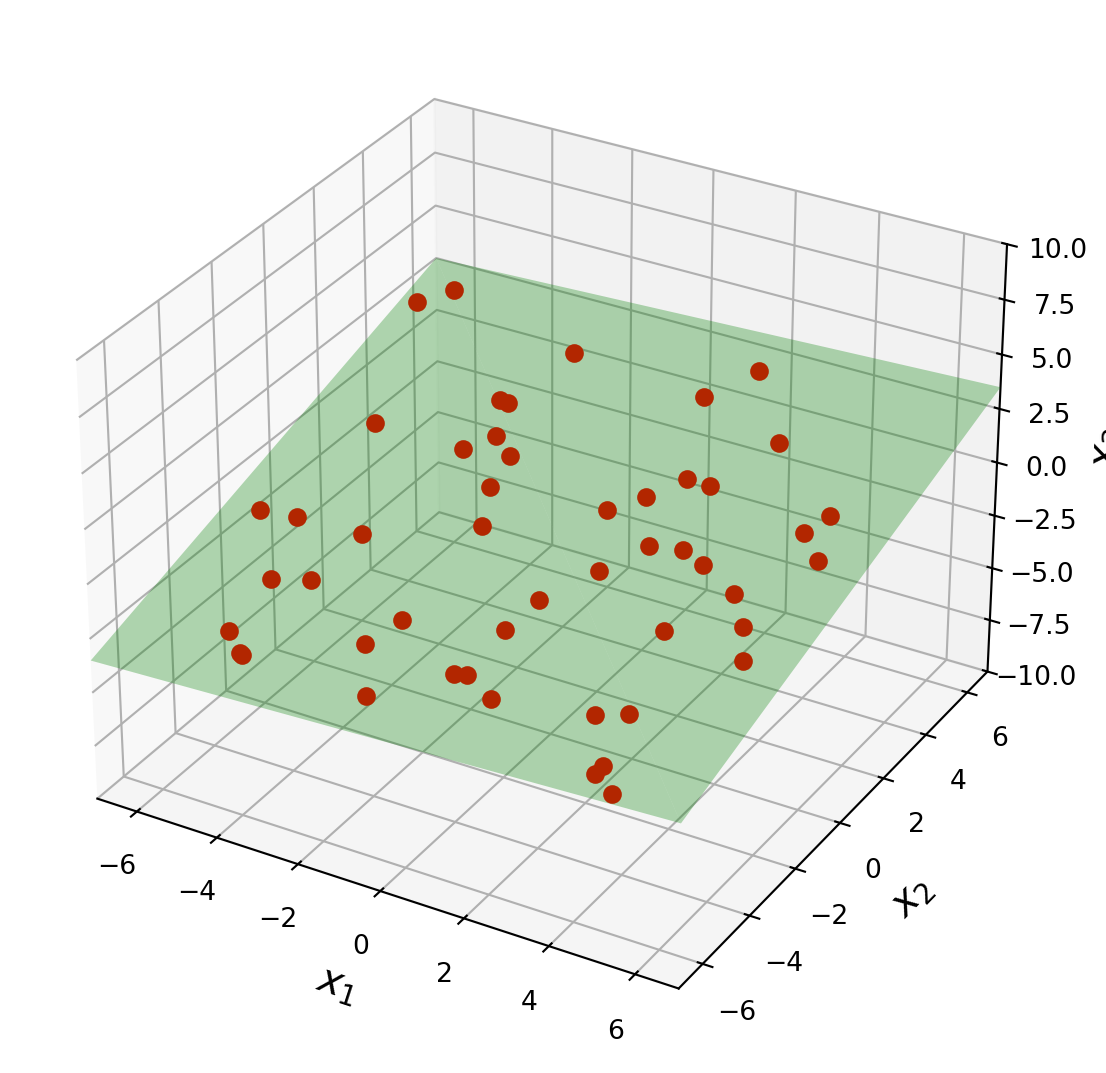

Let’s describe the linear models that gives a least-squares fit to such data.

The solution is called the least-squares plane.

We expect the data to satisfy these equations:

\[ \begin{align*} y_1 &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 u_1 + \beta_2 v_1 + \beta_3 z_1 + \epsilon_1, \\ y_2 &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 u_2 + \beta_2 v_2 + \beta_3 z_2 + \epsilon_2, \\ \vdots \\ y_n &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 u_n + \beta_2 v_n + \beta_3 z_n + \epsilon_n. \end{align*} \]

This system has the matrix for \(\mathbf{y} = X\mathbf{\beta} + \epsilon,\) where

\[ \mathbf{y} = \begin{bmatrix}y_1\\ y_1\\ \vdots\\ y_n \end{bmatrix},\;\; X = \begin{bmatrix}1&u_1&v_1&z_1\\ 1&u_2&v_2&z_2\\ \vdots&\vdots&\vdots&\vdots\\ 1&u_n&v_n&z_n \end{bmatrix},\;\; \mathbf{\beta}= \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0\\ \beta_1\\ \beta_2\\ \beta_3 \end{bmatrix},\;\; \epsilon = \begin{bmatrix} \epsilon_1\\ \epsilon_2\\ \vdots\\ \epsilon_n \end{bmatrix}. \]

ax = ut.plotSetup3d(-7, 7, -7, 7, -10, 10, figsize = (7, 7))

v = [4.0, 4.0, 2.0]

u = [-4.0, 3.0, 1.0]

# plotting the span of v

ut.plotSpan3d(ax,u,v,'Green')

npts = 50

ax.plot(coords[0], coords[1], 'ro', zs = coords[2], markersize=6)

plt.show()

This example shows that the linear model for multiple regression has the same form as the model for the simple regression in the earlier examples.

We can see that the general principle is the same across all the different kinds of linear models.

Once \(X\) is defined properly, the normal equations for \(\mathbf{\beta}\) have the same matrix form, no matter how many variables are involved.

Thus, for any linear model where \(X^TX\) is invertible, the least squares estimate is

\[ \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} = (X^TX)^{-1}X^T\mathbf{y}. \]

Given any \(X\) and \(\mathbf{y}\), the above algorithm will produce an output \(\hat{\beta}\).

But how do we know whether the data is in fact well described by the model?

The most common measure of fit is \(R^2\).

\(R^2\) measures the fraction of the variance of \(\mathbf{y}\) that can be explained by the model \(X\hat{\beta}\).

The variance of \(\mathbf{y}\) is

\[ \text{Var}(\mathbf{y}) =\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\overline{y}\right)^2, \]

where \(\overline{y}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^ny_i\).

For any given \(n\), we can equally work with just \[ \sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\overline{y}\right)^2, \]

which is called the Total Sum of Squares (TSS).

Now to measure the quality of fit of a model, we break TSS down into two components.

For any given \(\mathbf{x}_i\), the prediction made by the model is \(\hat{y_i} = \mathbf{x}_i^T\beta\).

We can break the total sum of squares into two parts:

Se we define the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) as:

\[ \text{RSS} = \sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\hat{y_i}\right)^2, \]

and the Explained Sum of Squares (ESS) as:

\[ \text{ESS} = \sum_{i=1}^n \left(\hat{y_i}-\overline{y}\right)^2, \]

One can show that the total sum of squares is exactly equal to the sum of squares of the residuals plus the sum of squares of the explained part.

In other words:

\[ \text{TSS} = \text{RSS} + \text{ESS}. \]

Given:

Proof:

Start by decomposing the deviation from the mean: \[y_i - \bar{y} = (y_i - \hat{y}_i) + (\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})\]

Square both sides: \[\begin{align} (y_i - \bar{y})^2 &= [(y_i - \hat{y}_i) + (\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})]^2\\ &= (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 + 2(y_i - \hat{y}_i)(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}) + (\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})^2 \end{align}\]

Sum over all \(i\): \[\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \bar{y})^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 + 2\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}) + \sum_{i=1}^n (\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})^2\]

Which gives us: \[\text{TSS} = \text{RSS} + 2\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}) + \text{ESS}\]

The key step: We need to show that the cross-term equals zero: \[\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}) = 0\]

Why is this zero?

For OLS regression with an intercept, the residuals \((y_i - \hat{y}_i)\) satisfy two orthogonality conditions:

Using condition (2): \[\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}) = \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)\hat{y}_i - \bar{y}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i) = 0 - \bar{y} \cdot 0 = 0\]

Therefore: TSS = RSS + ESS ✓

Geometric Intuition:

This decomposition is a Pythagorean theorem in high-dimensional space! The vectors \((y_i - \bar{y})\), \((y_i - \hat{y}_i)\), and \((\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})\) form a right triangle because the residuals are orthogonal to the fitted values.

Condition 1 is satisfied exactly (not just approximately), but this is only true when the model includes an intercept term.

When you include an intercept \(\beta_0\), the normal equations \(X^TX\beta = X^Ty\) include a row corresponding to the column of 1s in the design matrix.

Consider a linear model with an intercept. The design matrix has a column of 1s:

\[X = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_{11} & x_{12} & \cdots & x_{1p} \\ 1 & x_{21} & x_{22} & \cdots & x_{2p} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_{n1} & x_{n2} & \cdots & x_{np} \end{bmatrix}, \quad \beta = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \\ \vdots \\ \beta_p \end{bmatrix}, \quad y = \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{bmatrix}\]

The OLS solution satisfies the normal equations: \[X^T X \beta = X^T y\]

The transpose of \(X\) is: \[X^T = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ x_{11} & x_{21} & x_{31} & \cdots & x_{n1} \\ x_{12} & x_{22} & x_{32} & \cdots & x_{n2} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{1p} & x_{2p} & x_{3p} & \cdots & x_{np} \end{bmatrix}\]

The first row is all 1s!

The normal equations give us a system of \((p+1)\) equations. The first equation comes from multiplying the first row of \(X^T\) with both sides:

Left side: First row of \(X^T\) times \(X\beta\) \[[1, 1, 1, \ldots, 1] \cdot X\beta = \sum_{i=1}^n (X\beta)_i = \sum_{i=1}^n \hat{y}_i\]

Right side: First row of \(X^T\) times \(y\) \[[1, 1, 1, \ldots, 1] \cdot y = \sum_{i=1}^n y_i\]

Therefore, the first normal equation is: \[\boxed{\sum_{i=1}^n \hat{y}_i = \sum_{i=1}^n y_i}\]

This is exact, not approximate. It’s a direct consequence of having the column of 1s in \(X\).

Dividing by \(n\): \[\bar{\hat{y}} = \bar{y}\]

The mean of the fitted values equals the mean of the observed values. This is why, with an intercept, the regression line always passes through the point \((\bar{x}, \bar{y})\).

End of proof

If you force the regression through the origin (no \(\beta_0\) term), then:

The centered version assumes an intercept; the uncentered version doesn’t.

For standard OLS with intercept: - \(\sum (y_i - \hat{y}_i) = 0\) ✓ (exactly) - \(\sum (y_i - \hat{y}_i)\hat{y}_i = 0\) ✓ (exactly, from normal equations)

Both are mathematical properties, not approximations!

Now, a good fit is one in which the model explains a large part of the variance of \(\mathbf{y}\).

So the measure of fit \(R^2\) is defined as:

\[ R^2 = \frac{\text{ESS}}{\text{TSS}} = 1-\frac{\text{RSS}}{\text{TSS}} = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\hat{y_i}\right)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\overline{y}\right)^2}. \]

As a result, \(0\leq R^2\leq 1\).

This is more specifically called \(R^2\) centered.

There is also an uncentered version of \(R^2\) defined as:

\[ R^2 (\text{uncentered}) = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i-\hat{y_i}\right)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n y_i^2}. \]

The closer the value of \(R^2\) is to \(1\) the better the fit of the regression:

\(R^2\) is called the coefficient of determination.

It tells us “how well does the model predict the data?”

Do not confuse \(R^2\) with Pearson’s \(r\), which is the correlation coefficient.

(To make matters worse, sometimes people talk about \(r^2\)… very confusing!)

The correlation coefficient tells us whether two variables are correlated.

However, just because two variables are correlated does not mean that one is a good predictor of the other!

To compare ground truth with predictions, we always use \(R^2\).

First, we’ll look at a test case on synthetic data. We’ll use Scikit-Learn’s make_regression function.

from sklearn import datasets

X, y = datasets.make_regression(n_samples=100, n_features=20, n_informative=5, bias=0.1, noise=30, random_state=1)And then use the statsmodels package to fit the model.

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Add a constant (intercept) to the design matrix

#X_with_intercept = sm.add_constant(X)

#model = sm.OLS(y, X_with_intercept)

model = sm.OLS(y, X)

results = model.fit()And print the summary of the results.

print(results.summary()) OLS Regression Results

=======================================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared (uncentered): 0.969

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared (uncentered): 0.961

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 123.8

Date: Wed, 22 Oct 2025 Prob (F-statistic): 1.03e-51

Time: 22:31:23 Log-Likelihood: -468.30

No. Observations: 100 AIC: 976.6

Df Residuals: 80 BIC: 1029.

Df Model: 20

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

x1 12.5673 3.471 3.620 0.001 5.659 19.476

x2 -3.8321 2.818 -1.360 0.178 -9.440 1.776

x3 -2.4197 3.466 -0.698 0.487 -9.316 4.477

x4 2.0143 3.086 0.653 0.516 -4.127 8.155

x5 -2.6256 3.445 -0.762 0.448 -9.481 4.230

x6 0.7894 3.159 0.250 0.803 -5.497 7.076

x7 -3.0684 3.595 -0.853 0.396 -10.224 4.087

x8 90.1383 3.211 28.068 0.000 83.747 96.529

x9 -0.0133 3.400 -0.004 0.997 -6.779 6.752

x10 15.2675 3.248 4.701 0.000 8.804 21.731

x11 -0.2247 3.339 -0.067 0.947 -6.869 6.419

x12 0.0773 3.546 0.022 0.983 -6.979 7.133

x13 -0.2452 3.250 -0.075 0.940 -6.712 6.222

x14 90.0179 3.544 25.402 0.000 82.966 97.070

x15 1.6684 3.727 0.448 0.656 -5.748 9.085

x16 4.3945 2.742 1.603 0.113 -1.062 9.851

x17 8.7918 3.399 2.587 0.012 2.028 15.556

x18 73.3771 3.425 21.426 0.000 66.562 80.193

x19 -1.9139 3.515 -0.545 0.588 -8.908 5.080

x20 -1.3206 3.284 -0.402 0.689 -7.855 5.214

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 5.248 Durbin-Watson: 2.018

Prob(Omnibus): 0.073 Jarque-Bera (JB): 4.580

Skew: 0.467 Prob(JB): 0.101

Kurtosis: 3.475 Cond. No. 2.53

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] R² is computed without centering (uncentered) since the model does not contain a constant.

[2] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.The \(R^2\) value is very good. We can see that the linear model does a very good job of predicting the observations \(y_i\).

The summary uses the uncentered version of \(R^2\) because, as the footnote says, the model does not include a constant to account for an intercept term. You can try uncommenting the line X_with_intercept = sm.add_constant(X) and see that the summary then uses the centered version of \(R^2\).

Here is what all the statistics in the summary table mean:

where \(y_i\) is the actual value, and \(\hat{y}_i\) is the predicted value from the regression.

where \(n\) is the number of observations, and \(p\) is the number of predictors in the model.

where \(p\) is the number of predictors, and \(n\) is the number of observations.

where \(\sigma^2\) is the variance of the residuals.

where \(p\) is the number of parameters, and \(\mathcal{L}\) is the log-likelihood.

Definition: Similar to AIC, BIC penalizes models with more parameters, but more strongly than AIC. It is used to select among models.

Formula: \(\text{BIC} = p \log(n) - 2 \log(\mathcal{L})\)

where \(p\) is the number of parameters, \(n\) is the number of observations, and \(\mathcal{L}\) is the log-likelihood.

The first two columns are the independent variables and their coefficients. It is the \(m\) in \(y = mx + b\). One unit of change in the variable will affect the variable’s coefficient’s worth of change in the dependent variable. If the coefficient is negative, they have an inverse relationship. As one rises, the other falls.

The std error is an estimate of the standard deviation of the coefficient, a measurement of the amount of variation in the coefficient throughout its data points.

The t is related and is a measurement of the precision with which the coefficient was measured. A low std error compared to a high coefficient produces a high t statistic, which signifies a high significance for your coefficient.

P>|t| is one of the most important statistics in the summary. It uses the t statistic to produce the P value, a measurement of how likely your coefficient is measured through our model by chance. For example, a P value of 0.378 is saying there is a 37.8% chance the variable has no affect on the dependent variable and the results are produced by chance. Proper model analysis will compare the P value to a previously established alpha value, or a threshold with which we can apply significance to our coefficient. A common alpha is 0.05, which few of our variables pass in this instance.

[0.025 and 0.975] are both measurements of values of our coefficients within 95% of our data, or within two standard deviations. Outside of these values can generally be considered outliers.

The coefficient description came from this blog post which also describes the other statistics in the summary table.

Back to the example.

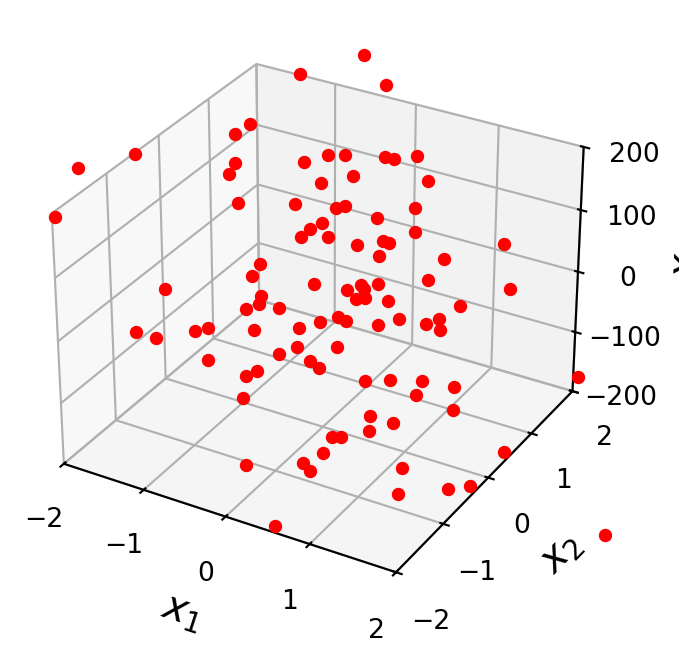

Some of the independent variables may not contribute to the accuracy of the prediction.

ax = ut.plotSetup3d(-2, 2, -2, 2, -200, 200)

# try columns of X with large coefficients, or not

ax.plot(X[:, 1], X[:, 2], 'ro', zs=y, markersize = 4)

Note that each parameter of an independent variable has an associated confidence interval.

If a coefficient is not distinguishable from zero, then we cannot assume that there is any relationship between the independent variable and the observations.

In other words, if the confidence interval for the parameter includes zero, the associated independent variable may not have any predictive value.

print('Confidence Intervals: {}'.format(results.conf_int()))

print('Parameters: {}'.format(results.params))Confidence Intervals: [[ 5.65891465 19.47559281]

[ -9.44032559 1.77614877]

[ -9.31636359 4.47701749]

[ -4.12661379 8.15524508]

[ -9.4808662 4.22965424]

[ -5.49698033 7.07574692]

[-10.22359973 4.08684835]

[ 83.74738375 96.52928603]

[ -6.77896356 6.75226985]

[ 8.80365396 21.73126149]

[ -6.86882065 6.4194618 ]

[ -6.97868351 7.1332267 ]

[ -6.71228582 6.2218515 ]

[ 82.96557061 97.07028228]

[ -5.74782503 9.08465366]

[ -1.06173893 9.85081724]

[ 2.02753258 15.5561241 ]

[ 66.56165458 80.19256546]

[ -8.90825108 5.0804296 ]

[ -7.85545335 5.21424811]]

Parameters: [ 1.25672537e+01 -3.83208841e+00 -2.41967305e+00 2.01431564e+00

-2.62560598e+00 7.89383294e-01 -3.06837569e+00 9.01383349e+01

-1.33468527e-02 1.52674577e+01 -2.24679428e-01 7.72715974e-02

-2.45217158e-01 9.00179264e+01 1.66841432e+00 4.39453916e+00

8.79182834e+00 7.33771100e+01 -1.91391074e+00 -1.32060262e+00]Find the independent variables that are not significant.

CIs = results.conf_int()

notSignificant = (CIs[:,0] < 0) & (CIs[:,1] > 0)

notSignificantarray([False, True, True, True, True, True, True, False, True,

False, True, True, True, False, True, True, False, False,

True, True])Let’s look at the shape of significant variables.

Xsignif = X[:,~notSignificant]

Xsignif.shape(100, 6)By eliminating independent variables that are not significant, we help avoid overfitting.

model = sm.OLS(y, Xsignif)

results = model.fit()

print(results.summary()) OLS Regression Results

=======================================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared (uncentered): 0.965

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared (uncentered): 0.963

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 437.1

Date: Wed, 22 Oct 2025 Prob (F-statistic): 2.38e-66

Time: 22:31:23 Log-Likelihood: -473.32

No. Observations: 100 AIC: 958.6

Df Residuals: 94 BIC: 974.3

Df Model: 6

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

x1 11.9350 3.162 3.775 0.000 5.657 18.213

x2 90.5841 2.705 33.486 0.000 85.213 95.955

x3 14.3652 2.924 4.913 0.000 8.560 20.170

x4 90.5586 3.289 27.535 0.000 84.028 97.089

x5 8.3185 3.028 2.747 0.007 2.307 14.330

x6 71.9119 3.104 23.169 0.000 65.749 78.075

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 9.915 Durbin-Watson: 2.056

Prob(Omnibus): 0.007 Jarque-Bera (JB): 11.608

Skew: 0.551 Prob(JB): 0.00302

Kurtosis: 4.254 Cond. No. 1.54

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] R² is computed without centering (uncentered) since the model does not contain a constant.

[2] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.Let’s see how powerful multiple regression can be on a real-world example.

A typical application of linear models is predicting house prices.

Linear models have been used for this problem for decades, and when a municipality does a value assessment on your house, they typically use a linear model.

We can consider various measurable attributes of a house (its “features”) as the independent variables, and the most recent sale price of the house as the dependent variable.

For our case study, we will use the features:

So our design matrix will have 8 columns (including the constant for the intercept):

\[ X\beta = \mathbf{y}, \]

and it will have one row for each house in the data set, with \(y\) the sale price of the house.

We will use data from housing sales in Ames, Iowa from 2006 to 2009:

Tim Kiser (w:User:Malepheasant) CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

df = pd.read_csv('data/ames-housing-data/train.csv')df[['LotArea', 'GrLivArea', 'Fireplaces', 'FullBath', 'HalfBath', 'GarageArea', 'TotalBsmtSF', 'SalePrice']].head()| LotArea | GrLivArea | Fireplaces | FullBath | HalfBath | GarageArea | TotalBsmtSF | SalePrice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8450 | 1710 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 548 | 856 | 208500 |

| 1 | 9600 | 1262 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 460 | 1262 | 181500 |

| 2 | 11250 | 1786 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 608 | 920 | 223500 |

| 3 | 9550 | 1717 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 642 | 756 | 140000 |

| 4 | 14260 | 2198 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 836 | 1145 | 250000 |

Some things to note here:

Do we have scaling concerns here?

No, because each feature will get its own \(\beta\), which will correct for the scaling differences between different units of measure.

X_no_intercept = df[['LotArea', 'GrLivArea', 'Fireplaces', 'FullBath', 'HalfBath', 'GarageArea', 'TotalBsmtSF']]

X_intercept = sm.add_constant(X_no_intercept)

y = df['SalePrice'].valuesNote that removing the intercept will cause the \(R^2\) to go up, which is counter-intuitive. The reason is explained here] – but amounts to the fact that the formula for R2 with/without an intercept is different.

Let’s split the data into training and test sets.

from sklearn import utils, model_selection

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = model_selection.train_test_split(

X_intercept, y, test_size = 0.5, random_state = 0)Fit the model to the training data.

model = sm.OLS(y_train, X_train)

results = model.fit()

print(results.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.759

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.757

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 325.5

Date: Wed, 22 Oct 2025 Prob (F-statistic): 1.74e-218

Time: 22:31:23 Log-Likelihood: -8746.5

No. Observations: 730 AIC: 1.751e+04

Df Residuals: 722 BIC: 1.755e+04

Df Model: 7

Covariance Type: nonrobust

===============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -4.285e+04 5350.784 -8.007 0.000 -5.34e+04 -3.23e+04

LotArea 0.2361 0.131 1.798 0.073 -0.022 0.494

GrLivArea 48.0865 4.459 10.783 0.000 39.332 56.841

Fireplaces 1.089e+04 2596.751 4.192 0.000 5787.515 1.6e+04

FullBath 1.49e+04 3528.456 4.224 0.000 7977.691 2.18e+04

HalfBath 1.56e+04 3421.558 4.559 0.000 8882.381 2.23e+04

GarageArea 98.9856 8.815 11.229 0.000 81.680 116.291

TotalBsmtSF 62.6392 4.318 14.508 0.000 54.163 71.116

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 144.283 Durbin-Watson: 1.937

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 917.665

Skew: 0.718 Prob(JB): 5.39e-200

Kurtosis: 8.302 Cond. No. 6.08e+04

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 6.08e+04. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.We see that we have:

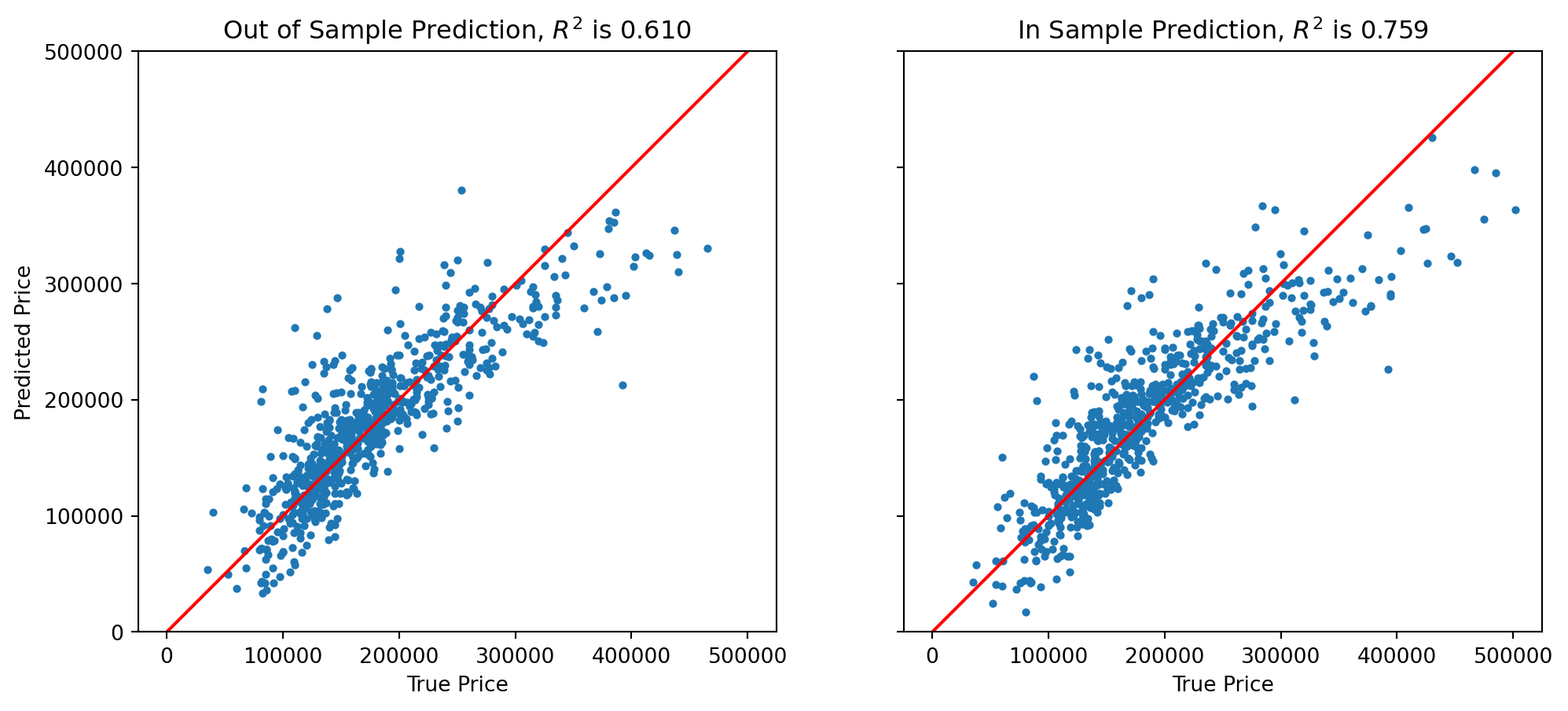

Is our model doing a good job?

There are many statistics for testing this question, but we’ll just look at the predictions versus the ground truth.

For each house we compute its predicted sale value according to our model:

\[ \hat{\mathbf{y}} = X\hat{\beta} \]

%matplotlib inline

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1,2,sharey = 'row', figsize=(12, 5))

y_oos_predict = results.predict(X_test)

r2_test = r2_score(y_test, y_oos_predict)

ax1.scatter(y_test, y_oos_predict, s = 8)

ax1.set_xlabel('True Price')

ax1.set_ylabel('Predicted Price')

ax1.plot([0,500000], [0,500000], 'r-')

ax1.axis('equal')

ax1.set_ylim([0, 500000])

ax1.set_xlim([0, 500000])

ax1.set_title(f'Out of Sample Prediction, $R^2$ is {r2_test:0.3f}')

#

y_is_predict = results.predict(X_train)

ax2.scatter(y_train, y_is_predict, s = 8)

r2_train = r2_score(y_train, y_is_predict)

ax2.set_xlabel('True Price')

ax2.plot([0,500000],[0,500000],'r-')

ax2.axis('equal')

ax2.set_ylim([0,500000])

ax2.set_xlim([0,500000])

ax2.set_title(f'In Sample Prediction, $R^2$ is {r2_train:0.3f}')

plt.show()

We see that the model does a reasonable job for house values less than about $250,000.

It tends to underestimate at both ends of the price range.

Note that the \(R^2\) on the (held out) test data is 0.610.

We are not doing as well on test data as on training data (somewhat to be expected).

For a better model, we’d want to consider more features of each house, and perhaps some additional functions such as polynomials as components of our model.