Time Series Analysis

Colab

Introduction to Time Series

What is a Time Series?

Time series = data points indexed by time (hourly, daily, monthly…)

Two key goals:

- Analysis: What patterns exist? Trends? Seasonality? Anomalies?

- Forecasting: What comes next?

Time Series Are Everywhere

| Domain | Example Questions |

|---|---|

| Finance | Will this stock go up? What’s my portfolio risk? |

| Healthcare | Is this patient’s vitals trending abnormally? |

| Climate | How much warmer will next decade be? |

| Retail | How much inventory do I need for Black Friday? |

The Four Components

Every time series can be decomposed into:

| Component | What it captures | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trend | Long-term direction | “Are EV sales growing?” |

| Seasonality | Fixed-period cycles | “Ice cream sales spike in summer” |

| Cyclic | Variable-length oscillations | “Business cycles” |

| Noise | Random variation | “Day-to-day fluctuations” |

Today’s Roadmap

- Visualize — See patterns before modeling

- Decompose — Separate trend, seasonality, noise

- Test — Is it stationary? (Spoiler: it matters)

- Model — AR, MA, ARIMA, SARIMA

- Forecast — Predict the future (with uncertainty)

Time and Date Manipulation

Many time series data sets are indexed by date or time. The python datetime library and the pandas library provide a powerful set of tools for manipulating time series data.

The Time Series chapter of the book Python for Data Analysis, 3rd Ed. provides a good overview of these tools. We’ll share a few excerpts here.

Code

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from datetime import datetime

now = datetime.now()

print(f"Date and time when this cell was executed: {now}")

print(f"Year: {now.year}, month: {now.month}, day: {now.day}")

delta = now - datetime(2024, 1, 1)

print(f"Since beginning of 2024 till when this cell was run there were {delta.days} days and {delta.seconds} seconds.")Date and time when this cell was executed: 2025-12-03 16:30:58.464698

Year: 2025, month: 12, day: 3

Since beginning of 2024 till when this cell was run there were 702 days and 59458 seconds.You can also convert between strings and datetime.

Code

# string to datetime

date_string = "2024-01-01"

date_object = datetime.strptime(date_string, "%Y-%m-%d")

print(date_object)2024-01-01 00:00:00You can also format datetime objects as strings.

Code

# datetime to string

now_str = now.strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

print(now_str)2025-12-03See Table 11.2 in the book for a list of formatting codes.

Let’s explore some of the pandas time series tools.

Create a time series with a datetime index.

Code

longer_ts = pd.Series(np.random.standard_normal(1000),

index=pd.date_range("2022-01-01", periods=1000))

print(type(longer_ts))

longer_ts<class 'pandas.core.series.Series'>2022-01-01 -0.364697

2022-01-02 0.640884

2022-01-03 -0.011666

2022-01-04 -0.175153

2022-01-05 -0.451890

...

2024-09-22 -0.097016

2024-09-23 2.367442

2024-09-24 0.451453

2024-09-25 -1.259707

2024-09-26 0.377718

Freq: D, Length: 1000, dtype: float64We can access just the samples from 2023 with simply:

Code

longer_ts["2023"]2023-01-01 -0.781808

2023-01-02 -1.518184

2023-01-03 -1.040690

2023-01-04 -1.086639

2023-01-05 -0.037886

...

2023-12-27 -1.268177

2023-12-28 -1.409587

2023-12-29 -0.575027

2023-12-30 0.966102

2023-12-31 -0.900605

Freq: D, Length: 365, dtype: float64Or the month of September 2023:

Code

longer_ts["2023-09"]2023-09-01 -0.060531

2023-09-02 0.877182

2023-09-03 -0.200798

2023-09-04 -0.288741

2023-09-05 0.757710

2023-09-06 -0.098894

2023-09-07 -1.227614

2023-09-08 -1.225380

2023-09-09 -0.063464

2023-09-10 0.451561

2023-09-11 -0.080826

2023-09-12 -0.341572

2023-09-13 -0.874473

2023-09-14 -0.625732

2023-09-15 -0.101654

2023-09-16 0.172896

2023-09-17 0.764761

2023-09-18 -1.296751

2023-09-19 -0.675250

2023-09-20 -0.933791

2023-09-21 -0.506061

2023-09-22 0.264288

2023-09-23 -0.425645

2023-09-24 0.744786

2023-09-25 -0.502617

2023-09-26 -0.492545

2023-09-27 0.016742

2023-09-28 1.071485

2023-09-29 -0.378090

2023-09-30 1.481958

Freq: D, dtype: float64Or slice by date range:

Code

longer_ts["2023-03-01":"2023-03-10"]2023-03-01 0.763007

2023-03-02 -0.336728

2023-03-03 0.157101

2023-03-04 -1.294433

2023-03-05 -0.978700

2023-03-06 2.237288

2023-03-07 -0.200754

2023-03-08 0.889437

2023-03-09 -1.712322

2023-03-10 0.241580

Freq: D, dtype: float64or:

Code

longer_ts["2023-09-15":]2023-09-15 -0.101654

2023-09-16 0.172896

2023-09-17 0.764761

2023-09-18 -1.296751

2023-09-19 -0.675250

...

2024-09-22 -0.097016

2024-09-23 2.367442

2024-09-24 0.451453

2024-09-25 -1.259707

2024-09-26 0.377718

Freq: D, Length: 378, dtype: float64There are many more time series tools available that let you do things like:

- Shifting and setting frequencies of date ranges

- Time zone handling

- Time series resampling

- Time series rolling and expanding windows

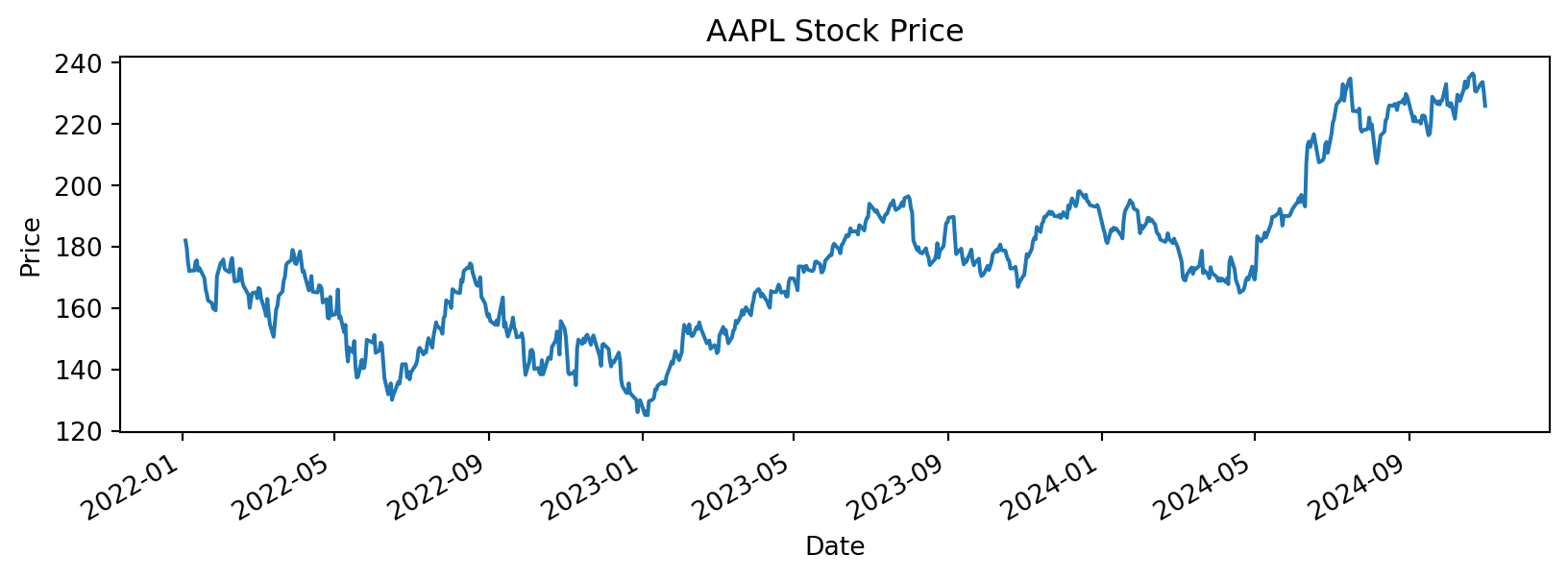

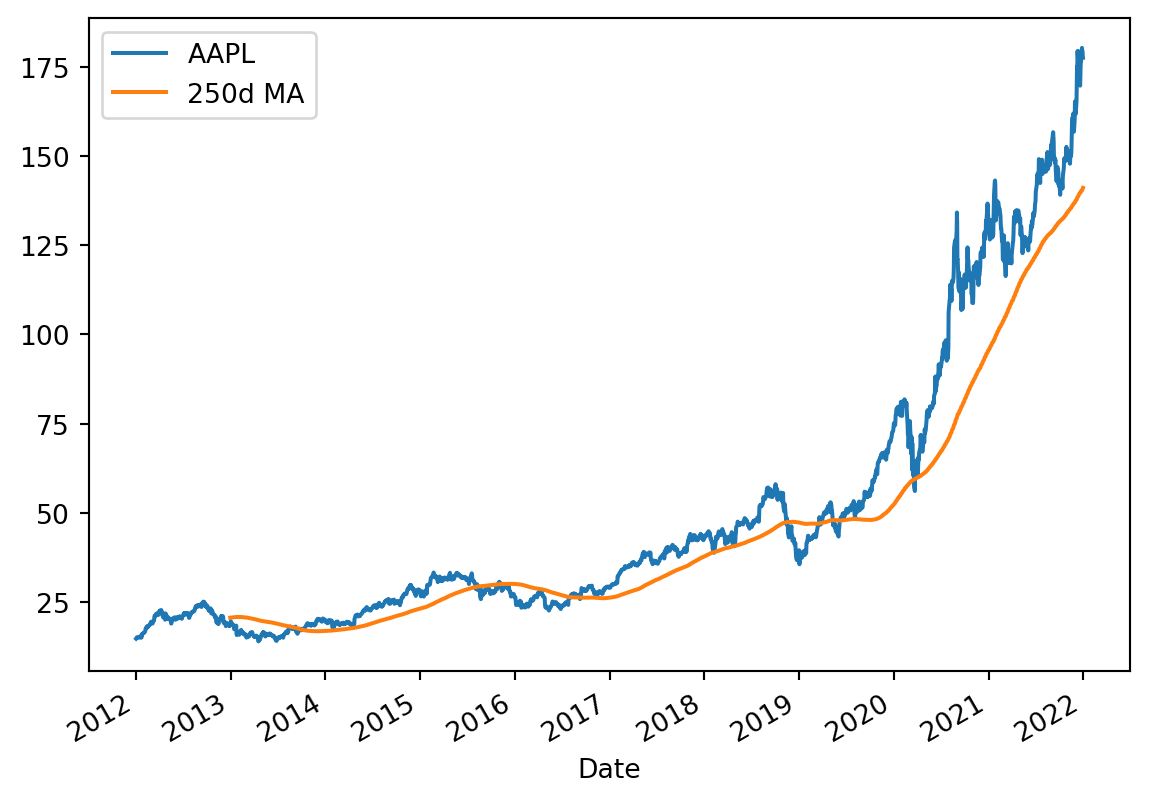

Moving Window Functions

Let’s dive into the moving window functions.

Code

import pandas as pd

import yfinance as yf

import os

# Define the file path for cached data (10-year history)

aapl_10yr_file_path = os.path.join('data', 'aapl_stock_data_10yr.csv')

# Check if the file exists and load it, otherwise download

import warnings

aapl_data = None

if os.path.exists(aapl_10yr_file_path):

# Load data from file - yfinance creates multi-level headers, skip rows 1,2

aapl_data = pd.read_csv(aapl_10yr_file_path, header=0, skiprows=[1, 2], index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

else:

# Download data from yfinance

try:

aapl_data = yf.download('AAPL', start='2012-01-01', end='2022-01-01', progress=False)

# Check if download was successful (non-empty dataframe)

if aapl_data.empty:

warnings.warn("Downloaded data is empty. Please check the ticker symbol and date range.")

aapl_data = None

else:

# Flatten columns if MultiIndex (yfinance >= 0.2.40)

if isinstance(aapl_data.columns, pd.MultiIndex):

aapl_data.columns = aapl_data.columns.get_level_values(0)

# Save to file for future use

aapl_data.to_csv(aapl_10yr_file_path)

except Exception as e:

warnings.warn(f"Error downloading data from yfinance: {str(e)}")

aapl_data = None

if aapl_data is not None:

print(aapl_data.head())

aapl_close_px = aapl_data['Close']

else:

print("AAPL data not available - skipping this example")/tmp/ipykernel_4829/2732215069.py:18: FutureWarning:

YF.download() has changed argument auto_adjust default to True

Price Close High Low Open Volume

Date

2012-01-03 12.333219 12.371308 12.266339 12.278336 302220800

2012-01-04 12.399497 12.436687 12.274735 12.296328 260022000

2012-01-05 12.537157 12.552752 12.376405 12.444785 271269600

2012-01-06 12.668217 12.678713 12.572845 12.589340 318292800

2012-01-09 12.648124 12.828670 12.636727 12.761191 394024400Code

# Plot the closing prices

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

if aapl_data is not None:

ax = aapl_close_px.plot(label='AAPL')

aapl_close_px.rolling(window=250).mean().plot(label='250d MA', ax=ax)

ax.legend()

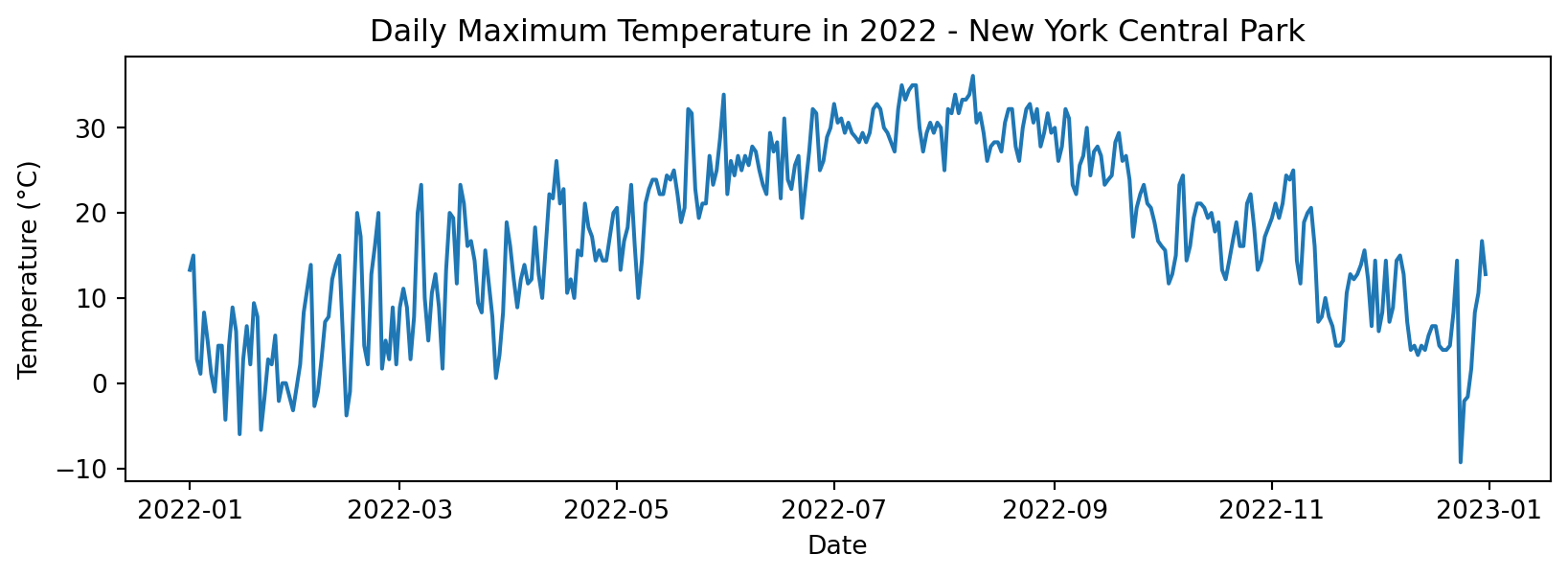

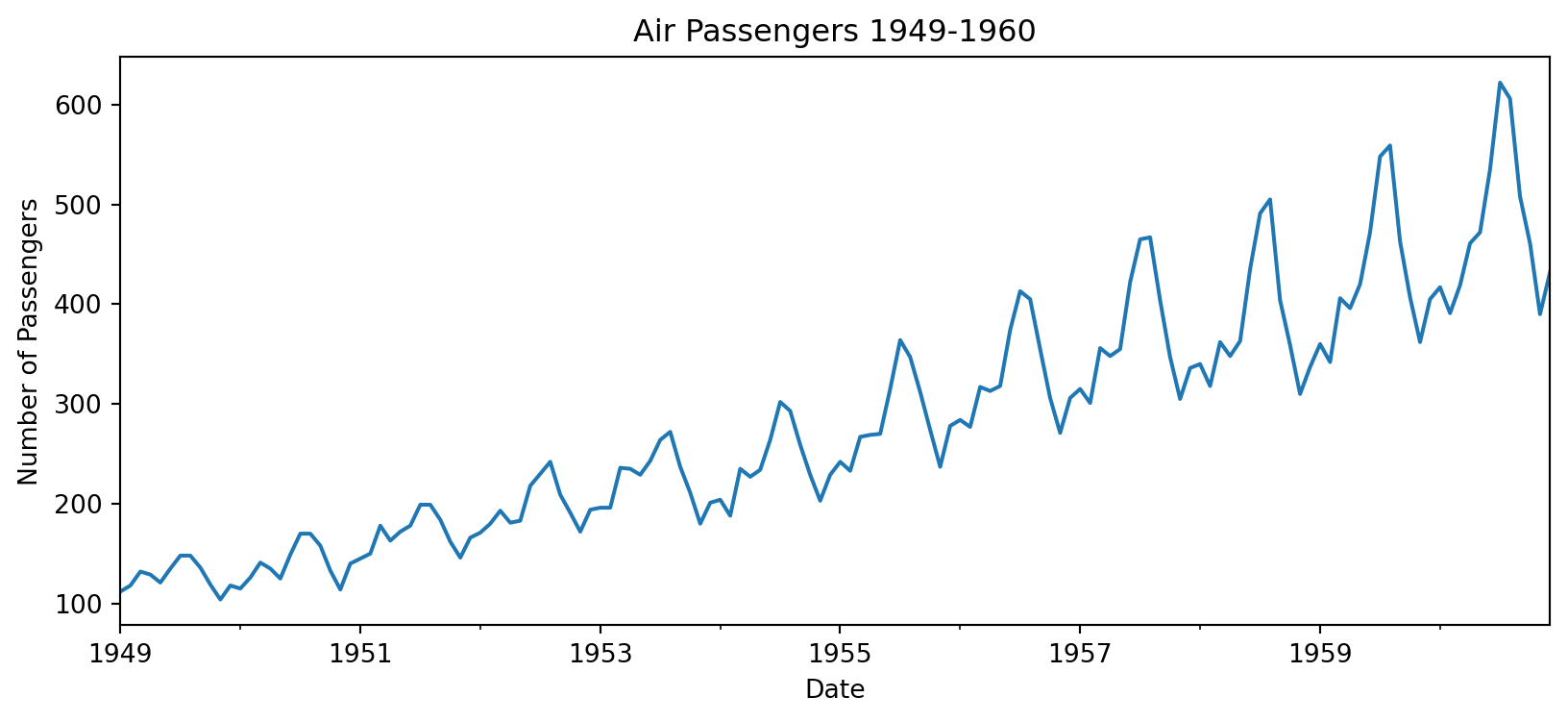

Visualization

Always visualize first! Let’s explore patterns in a classic dataset.

Air Passengers Dataset

We’re going to use a dataset of air passengers per month from 1949 to 1960.

Code

path = os.path.join('data', 'air_passengers_1949_1960.csv')

air_passengers = pd.read_csv(path, index_col='Date', parse_dates=True)

air_passengers.head()| Number of Passengers | |

|---|---|

| Date | |

| 1949-01-01 | 112 |

| 1949-02-01 | 118 |

| 1949-03-01 | 132 |

| 1949-04-01 | 129 |

| 1949-05-01 | 121 |

Time Series Plot

Let’s look at the time series plot.

Code

ts = air_passengers['Number of Passengers']

ts.plot(ylabel='Number of Passengers', title='Air Passengers 1949-1960', figsize=(10, 4))

Clearly there are some trends and seasonality in the data.

Clearly: trend (going up) + seasonality (annual pattern) + growing amplitude.

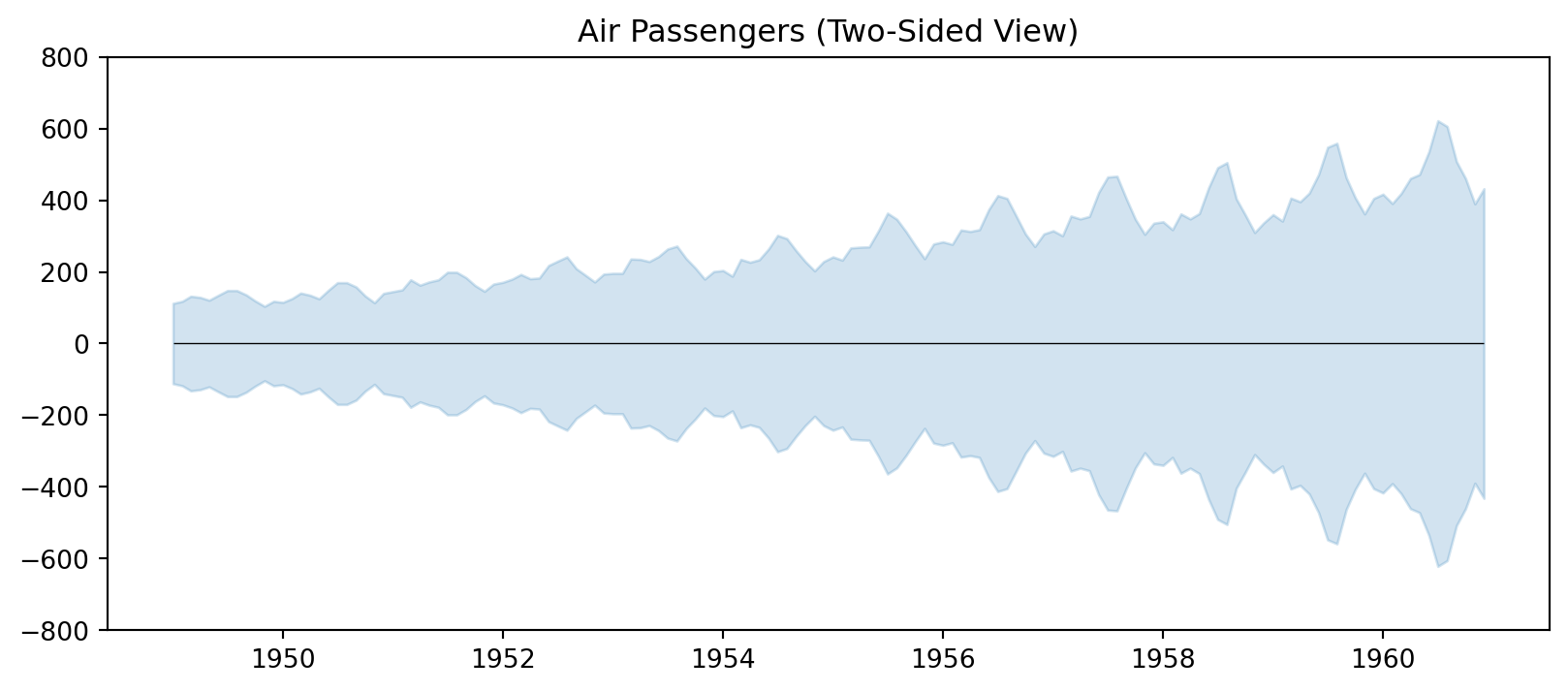

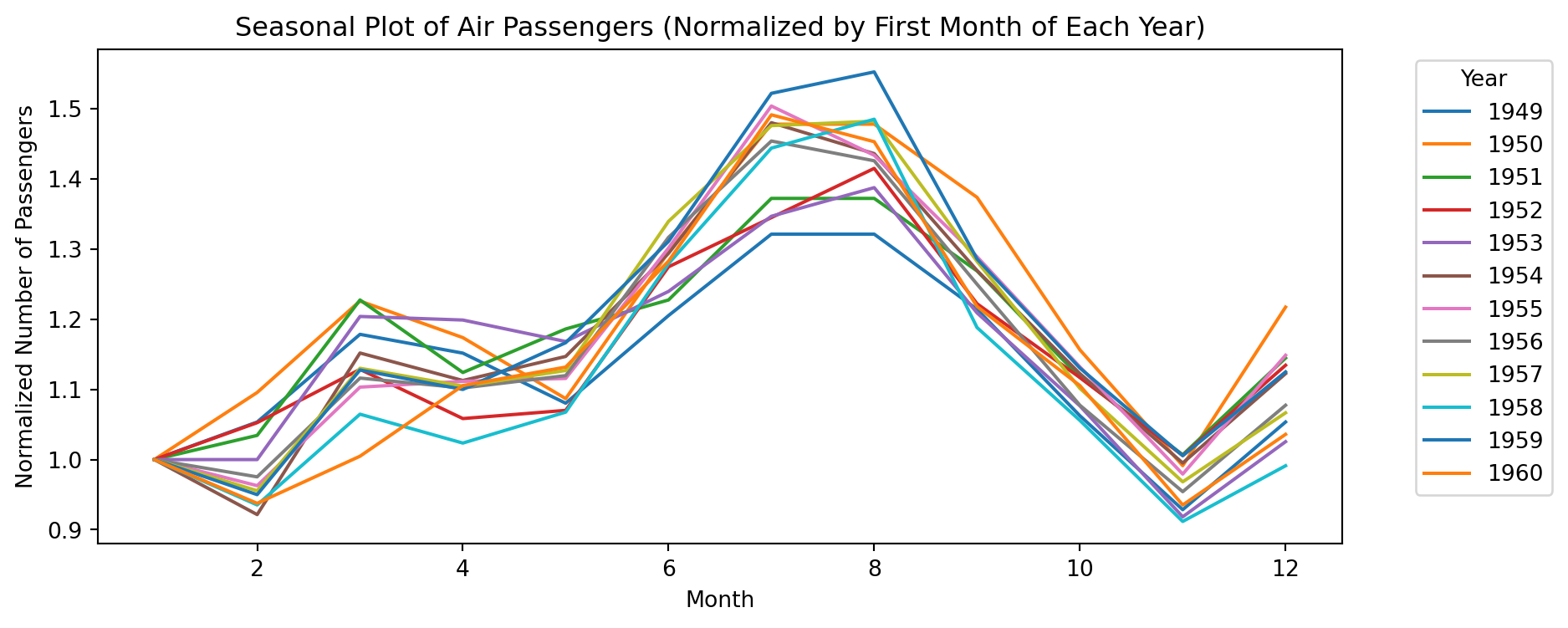

Let’s visualize that seasonal pattern more explicitly:

Code

# Seasonal plot of air_passengers

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Extract month and year from the index

air_passengers['Month'] = air_passengers.index.month

air_passengers['Year'] = air_passengers.index.year

# Create a seasonal plot

#plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

sns.lineplot(data=air_passengers, x='Month', y='Number of Passengers', hue='Year', palette='tab10')

# plt.title('Seasonal Plot of Air Passengers')

# plt.ylabel('Number of Passengers')

# plt.xlabel('Month')

# plt.legend(title='Year', bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1), loc='upper left')

# plt.show()

Notice: the seasonal amplitude is growing over time — important for model choice!

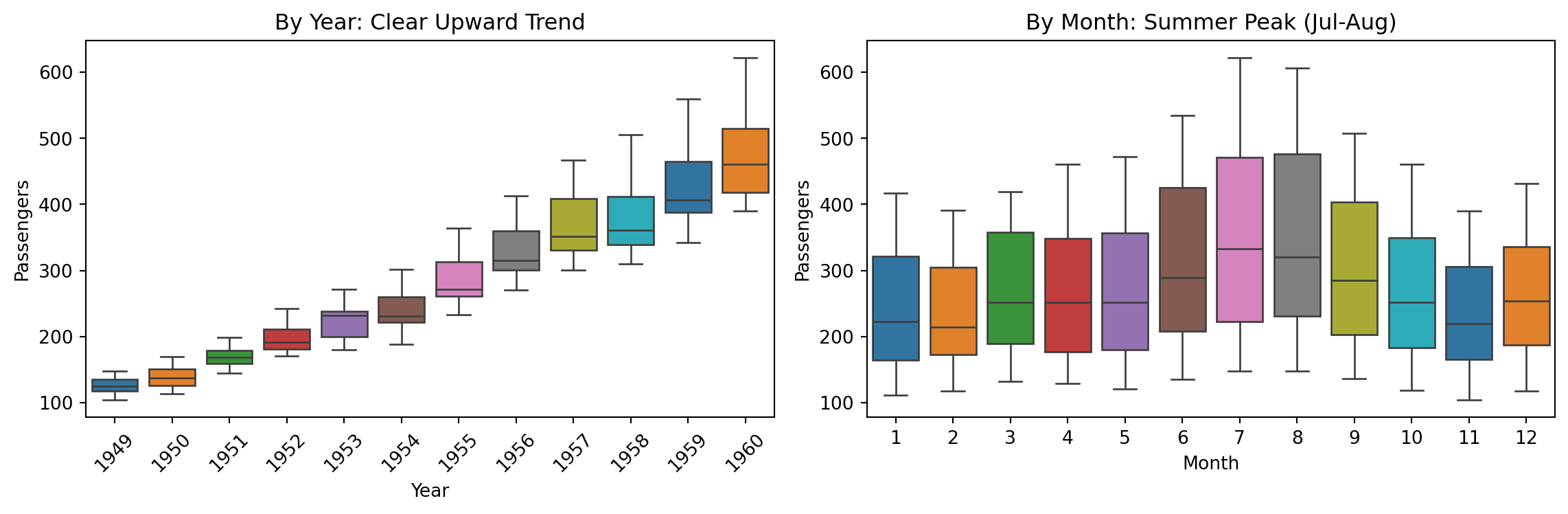

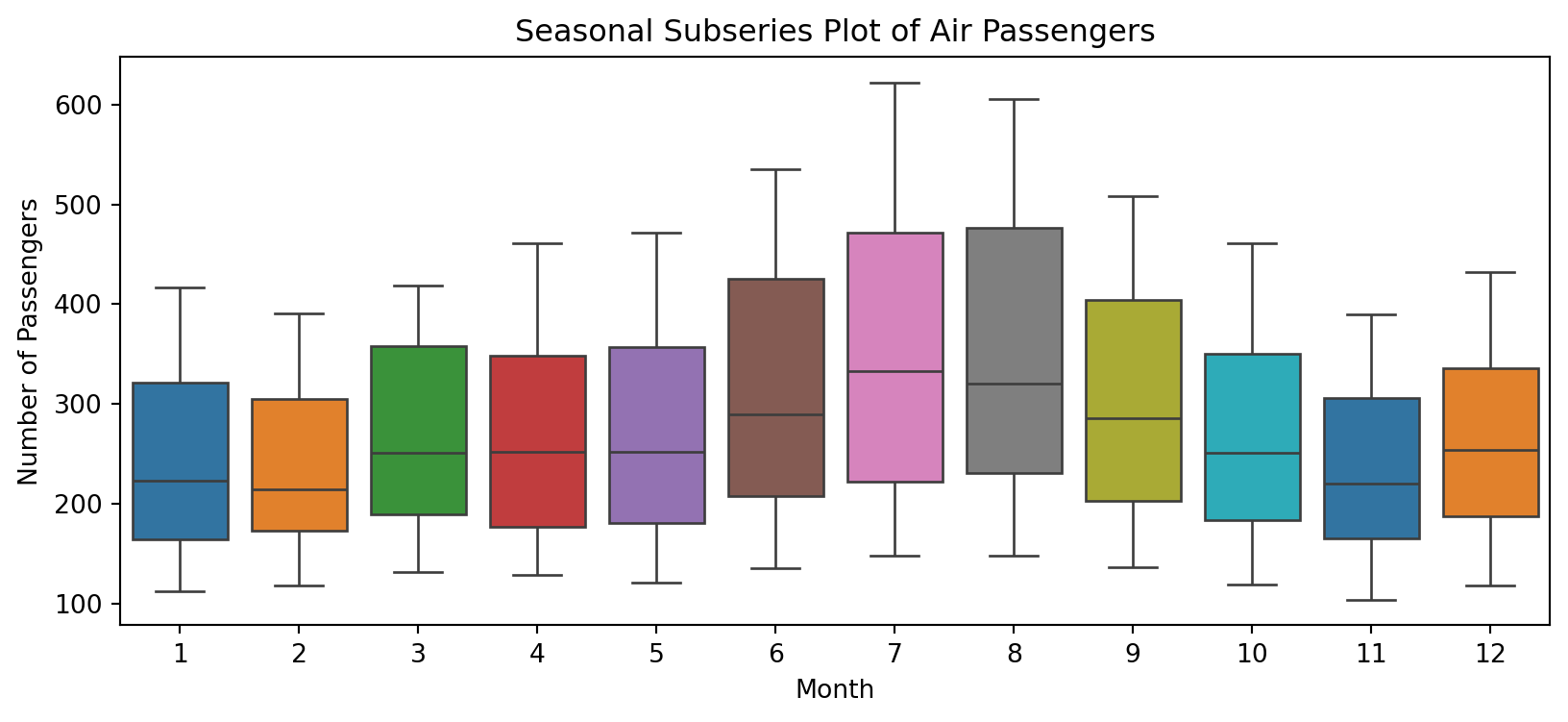

Let’s look at the distribution across years and months:

Code

# Add normalized column for later use

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

air_passengers['Normalized_Passengers'] = air_passengers.groupby('Year')['Number of Passengers'].transform(lambda x: x / x.iloc[0])

# Create side-by-side plots

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

# Year-wise box plot

sns.boxplot(data=air_passengers, x='Year', y='Number of Passengers', palette='tab10', ax=ax1)

ax1.set_title('By Year: Clear Upward Trend')

ax1.set_ylabel('Passengers')

ax1.tick_params(axis='x', rotation=45)

# Month-wise box plot

sns.boxplot(data=air_passengers, x='Month', y='Number of Passengers', palette='tab10', hue='Month', legend=False, ax=ax2)

ax2.set_title('By Month: Summer Peak (Jul-Aug)')

ax2.set_ylabel('Passengers')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()/tmp/ipykernel_4829/2554698556.py:9: FutureWarning:

Passing `palette` without assigning `hue` is deprecated and will be removed in v0.14.0. Assign the `x` variable to `hue` and set `legend=False` for the same effect.

Left: Trend is obvious. Right: July-August are peak travel months.

Box plot: median, Q1-Q3 Interquartile Range, Whiskers: \(1.5\times \text{IQR}\)

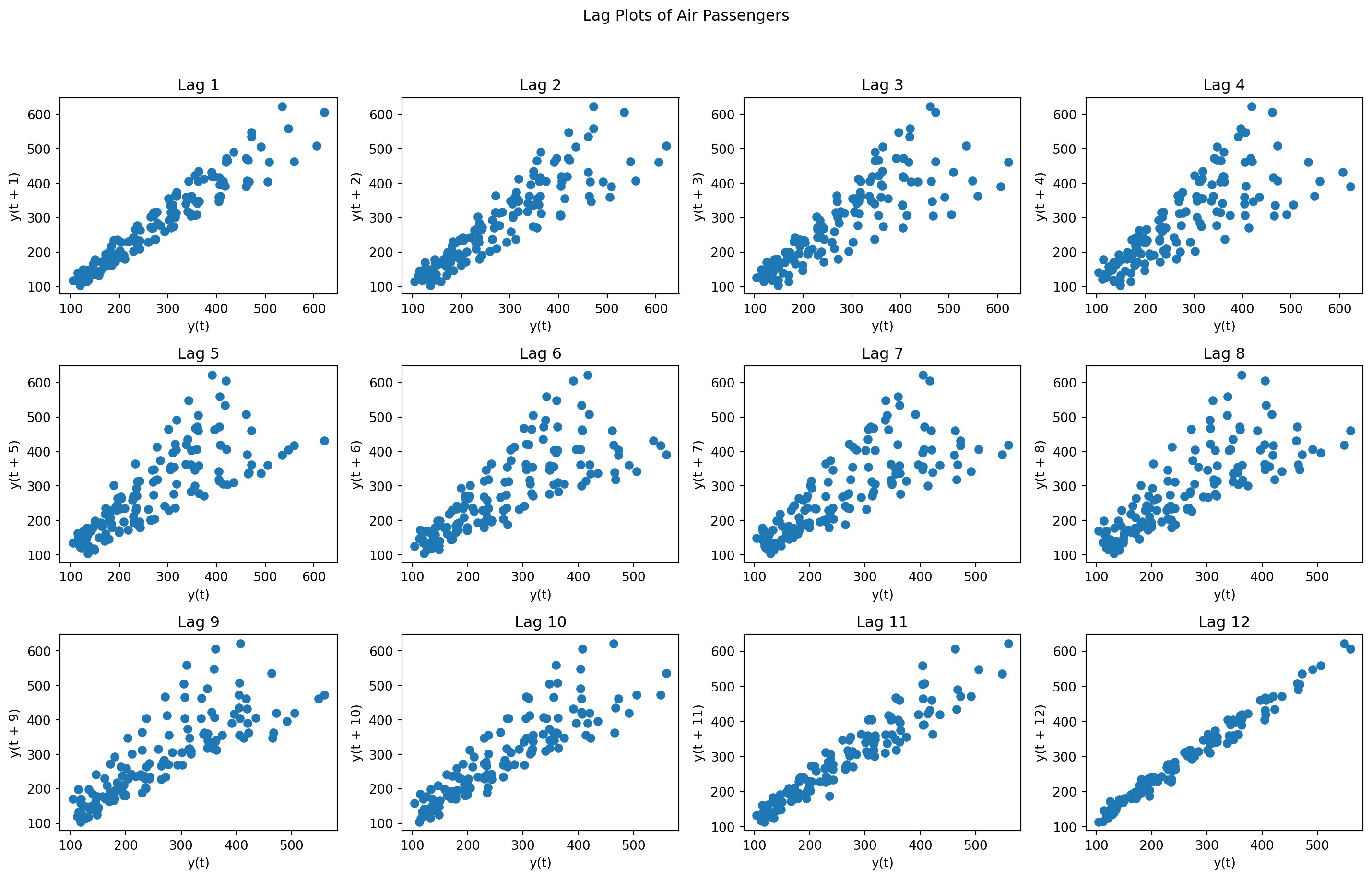

Autocorrelation: The Key Diagnostic

Autocorrelation = correlation between \(y_t\) and \(y_{t-k}\) (lagged by \(k\) steps)

\[ \rho_k = \frac{\sum_{t=k+1}^{T} (y_t - \bar{y})(y_{t-k} - \bar{y})}{\sum_{t=1}^{T} (y_t - \bar{y})^2} \]

Why it matters:

- High autocorrelation (for \(k>0\)) → values depend on past → predictable!

- Peaks at regular lags → seasonality

- No autocorrelation → white noise (unpredictable)

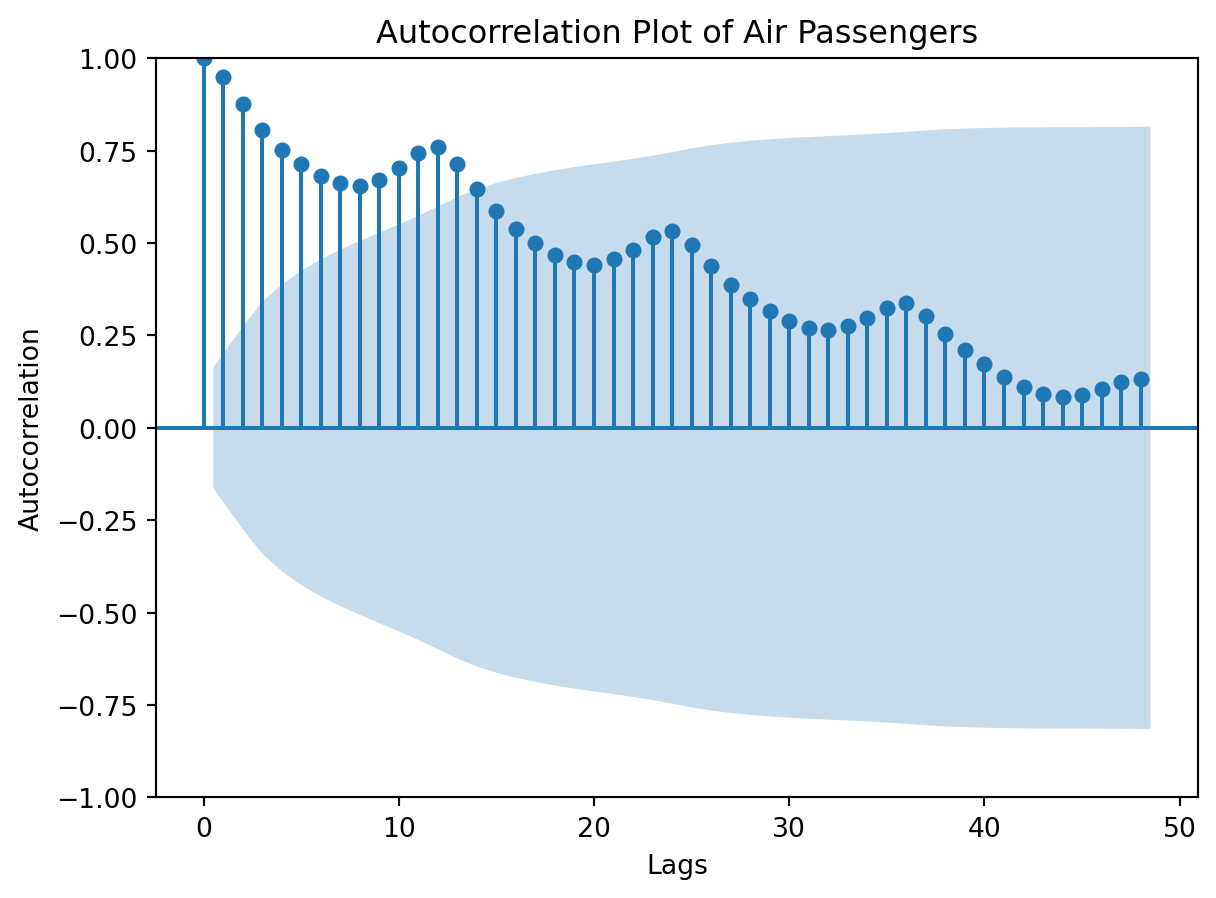

ACF of Air Passengers

Code

from statsmodels.graphics.tsaplots import plot_acf

plot_acf(air_passengers['Number of Passengers'], lags=48)

plt.title('Autocorrelation Plot of Air Passengers')

plt.show()

Reading the ACF: Blue shading = 95% CI. Peak at lag 12 is significant → yearly seasonality confirmed!

Time Series Decomposition

The Goal: Separate Signal from Noise

We want to break apart: Observed = Trend + Seasonality + Residual

Why?

- Understand the underlying patterns

- Remove seasonality for cleaner modeling

- Detect anomalies in the residuals

- Forecast each component separately

Additive vs Multiplicative

How do the components combine?

| Model | Formula | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| Additive | \(Y = T + S + \epsilon\) | Seasonal amplitude is constant |

| Multiplicative | \(Y = T \times S \times \epsilon\) | Seasonal amplitude grows with trend |

Look back at air passengers: amplitude grows → multiplicative is better!

Classical Decomposition: The Algorithm

Steps:

- Estimate trend — moving average smooths out seasonality

- Remove trend — detrended = observed - trend

- Estimate seasonality — average each month’s detrended values

- Residual — what’s left after removing trend & seasonality

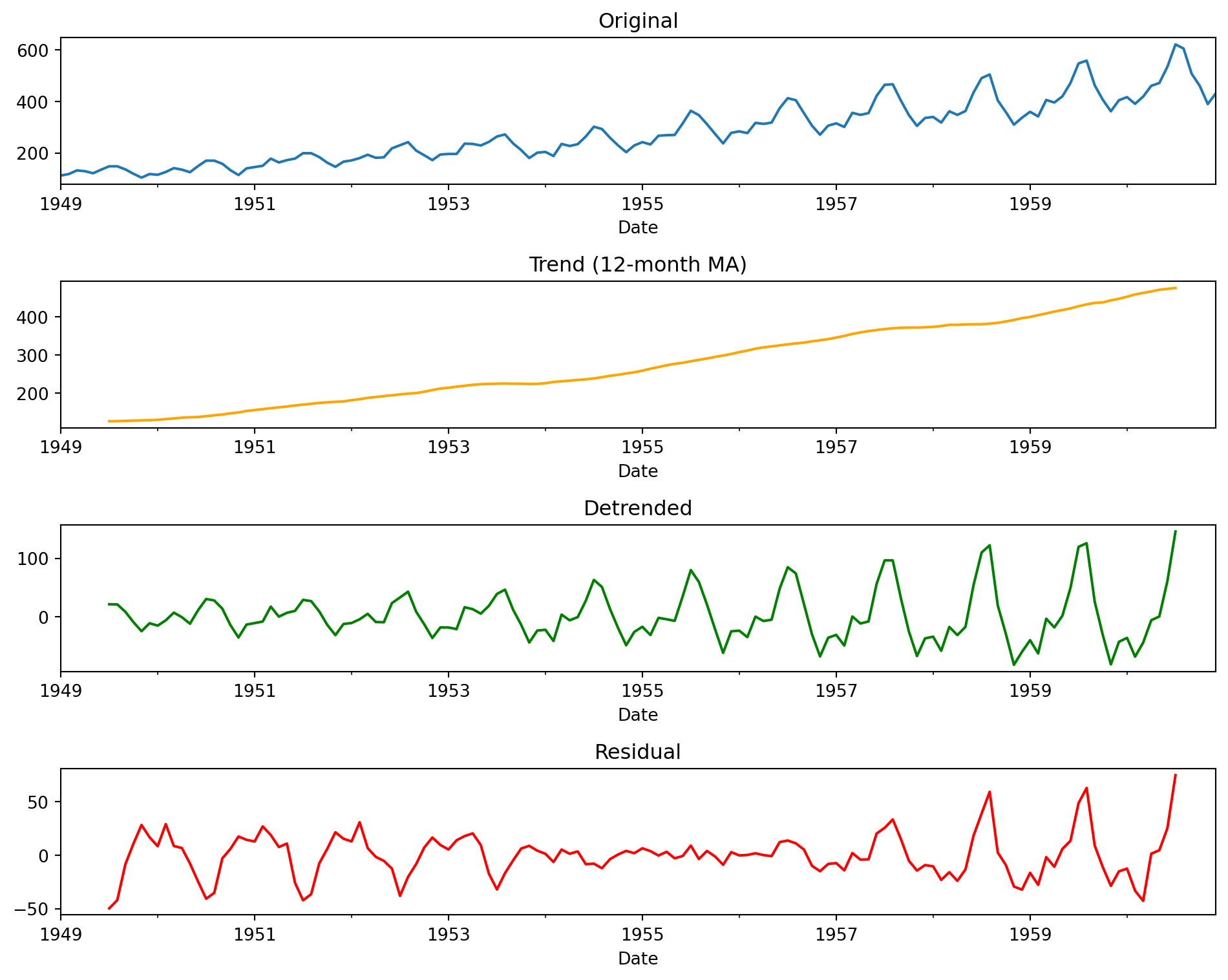

Let’s do it step by step:

Code

import numpy as np

# Step 1: Trend via moving average

trend = ts.rolling(window=12, center=True).mean()

# Step 2: Detrend

detrended_ts = ts - trend

# Step 3: Seasonal pattern (average by month)

seasonal_ts = detrended_ts.groupby(detrended_ts.index.month).mean()

# Step 4: Residual

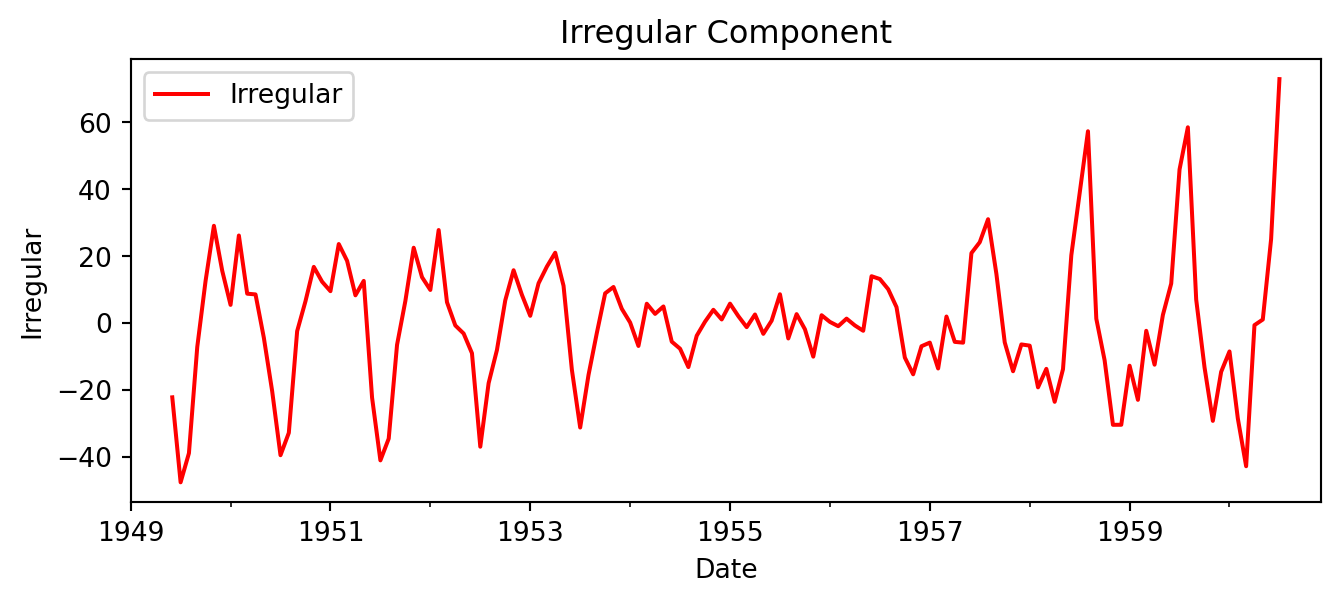

irregular_ts = detrended_ts - np.tile(seasonal_ts, len(detrended_ts) // len(seasonal_ts))

# Plot all components

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4, 1, figsize=(10, 8), sharex=False)

ts.plot(ax=axes[0], title='Original')

trend.plot(ax=axes[1], title='Trend (12-month MA)', color='orange')

detrended_ts.plot(ax=axes[2], title='Detrended', color='green')

irregular_ts.plot(ax=axes[3], title='Residual', color='red')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Question: Is the residual truly random? (Hint: look at the variance over time)

STL: A Better Decomposition

STL = Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess (Cleveland et al. 1990)

Why STL over classical?

- ✅ Handles changing seasonality (amplitude can vary)

- ✅ Robust to outliers

- ✅ Works with any period (not just 12 months)

See course notes for details on Loess (locally weighted regression)

Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing – Loess1

Loess, which stands for “Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing,” is a non-parametric method used to estimate non-linear relationships in data. It is particularly useful for smoothing scatterplots and is a type of local regression.

Key Features of Loess:

Local Fitting: Loess fits simple models to localized subsets of the data to build up a function that describes the deterministic part of the variation in the data, point by point.

Weighted Least Squares: It uses weighted least squares to fit a polynomial surface to the data. The weights decrease with distance from the point of interest, giving more influence to points near the target point.

Flexibility: Loess is flexible and can model complex relationships without assuming a specific global form for the data. It can adapt to various shapes and patterns in the data.

Smoothing Parameter: The degree of smoothing is controlled by a parameter, often denoted as \(\alpha\) or the span. This parameter determines the proportion of data points used in each local fit. A smaller span results in a curve that follows the data more closely, while a larger span results in a smoother curve.

Polynomial Degree: Loess can fit either linear or quadratic polynomials to the data. The choice of polynomial degree affects the smoothness and flexibility of the fit.

How Loess Works:

- Step 1: For each point in the dataset, a neighborhood of points is selected based on the smoothing parameter.

- Step 2: A weighted least squares regression is performed on the points in the neighborhood, with weights decreasing with distance from the target point.

- Step 3: The fitted value at the target point is computed from the local regression model.

- Step 4: This process is repeated for each point in the dataset, resulting in a smooth curve that captures the underlying trend.

Applications:

Loess is widely used in exploratory data analysis to visualize trends and patterns in data. It is particularly useful when the relationship between variables is complex and not well-represented by a simple linear or polynomial model.

Example in Python:

In Python, the statsmodels library provides a function for performing Loess smoothing:

Code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from statsmodels.nonparametric.smoothers_lowess import lowess

# Example data

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

y = np.sin(x) + np.random.normal(0, 0.1, 100)

# Apply Loess smoothing

smoothed = lowess(y, x, frac=0.2)

# Plot

plt.scatter(x, y, label='Data', alpha=0.5)

plt.plot(smoothed[:, 0], smoothed[:, 1], color='red', label='Loess Smoothed')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

In this example, frac is the smoothing parameter that controls the amount of smoothing applied to the data.

In Practice: statsmodels

from statsmodels.tsa.seasonal import seasonal_decompose, STL

# Reload clean data

data = pd.read_csv(os.path.join('data', 'air_passengers_1949_1960.csv'), index_col='Date', parse_dates=True)

ts = data['Number of Passengers']Additive vs Multiplicative: See the Difference

Code

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 4, figsize=(14, 6))

for i, model in enumerate(['additive', 'multiplicative']):

decomp = seasonal_decompose(ts, model=model)

decomp.observed.plot(ax=axes[i, 0], title='Observed' if i==0 else '')

decomp.trend.plot(ax=axes[i, 1], title='Trend' if i==0 else '')

decomp.seasonal.plot(ax=axes[i, 2], title='Seasonal' if i==0 else '')

decomp.resid.plot(ax=axes[i, 3], title='Residual' if i==0 else '')

axes[i, 0].set_ylabel(model.title())

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Key insight: Multiplicative residuals are more uniform — better fit!

STL in Action

Code

from statsmodels.tsa.seasonal import STL

stl = STL(ts, period=12, robust=True)

result = stl.fit()

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4, 1, figsize=(10, 6), sharex=True)

result.observed.plot(ax=axes[0], title='STL Decomposition')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Observed')

result.trend.plot(ax=axes[1])

axes[1].set_ylabel('Trend')

result.seasonal.plot(ax=axes[2])

axes[2].set_ylabel('Seasonal')

result.resid.plot(ax=axes[3])

axes[3].set_ylabel('Residual')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Stationarity: Why It Matters

The Stationarity Problem

Stationary = statistical properties (mean, variance) don’t change over time

Why do we care?

Most forecasting models assume stationarity.

If your data has:

- 📈 Trend → mean is changing

- 📊 Growing variance → variance is changing

- 🔄 Seasonality → periodic non-stationarity

…the model will fail. We must transform the data first.

Making Data Stationary

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Trend | Differencing: \(y'_t = y_t - y_{t-1}\) |

| Growing variance | Log transform: \(y'_t = \log(y_t)\) |

| Seasonality | Seasonal differencing: \(y'_t = y_t - y_{t-12}\) |

Testing for Stationarity

Two standard tests (both in statsmodels):

| Test | Null Hypothesis | Reject means… |

|---|---|---|

| ADF | Has unit root (non-stationary) | Stationary ✓ |

| KPSS | Is stationary | Non-stationary ✗ |

ADF (Augmented Dickey-Fuller): Tests whether a “unit root” is present — a mathematical property that causes non-stationarity. The test includes lagged differences to handle autocorrelation. If p-value < 0.05, reject the null → evidence the series is stationary.

KPSS (Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin): Flips the hypothesis — assumes stationarity and tests for evidence against it. Checks stats on residuals of the trend-stationary series. If p-value < 0.05, reject the null → evidence the series is non-stationary.

Stationarity Tests Continued

Why use both? They have opposite null hypotheses, so using them together provides stronger evidence:

| ADF Result | KPSS Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Reject (p<0.05) | Fail to reject | Stationary ✓ |

| Fail to reject | Reject (p<0.05) | Non-stationary ✗ |

| Both reject | Both reject | Trend-stationary (difference needed) |

| Neither rejects | Neither rejects | Inconclusive — gather more data |

See course notes for worked examples of ADF and KPSS tests

ADF Test Demonstration

Let’s apply the tests, starting with ADF:

Code

import pandas as pd

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller, kpss

air_passengers = pd.read_csv(os.path.join('data', 'air_passengers_1949_1960.csv'))

# Apply ADF and KPSS tests on the air passenger data

# ADF Test

result_adf = adfuller(air_passengers['Number of Passengers'])

print('ADF Statistic:', result_adf[0])

print('p-value:', result_adf[1])

print('Critical Values:')

for key, value in result_adf[4].items():

print('\t%s: %.3f' % (key, value))ADF Statistic: 0.8153688792060498

p-value: 0.991880243437641

Critical Values:

1%: -3.482

5%: -2.884

10%: -2.579Interpretation:

ADF Statistic: The ADF statistic is 0.815, which is greater than all the critical values at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels.

p-value: The p-value is 0.991, which is significantly higher than common significance levels (e.g., 0.01, 0.05, 0.10).

Critical Values:

- 1%: -3.482

- 5%: -2.884

- 10%: -2.579

Conclusion:

Fail to Reject the Null Hypothesis: Since the ADF statistic (0.815) is greater than the critical values and the p-value (0.991) is much higher than typical significance levels, you fail to reject the null hypothesis. This suggests that the time series has a unit root and is non-stationary.

Implication: The time series data for the number of passengers is non-stationary, indicating that it may have a trend or other non-stationary components. To make the series stationary, you might consider differencing the data or applying other transformations, such as detrending or seasonal adjustment, before proceeding with further analysis or modeling.

KPSS Test Demonstration

Let’s apply the KPSS test.

Code

# KPSS Test

result_kpss = kpss(air_passengers['Number of Passengers'], regression='c')

print('\nKPSS Statistic:', result_kpss[0])

print('p-value:', result_kpss[1])

print('Critical Values:')

for key, value in result_kpss[3].items():

print('\t%s: %.3f' % (key, value))

KPSS Statistic: 1.6513122354165206

p-value: 0.01

Critical Values:

10%: 0.347

5%: 0.463

2.5%: 0.574

1%: 0.739/tmp/ipykernel_4829/3460980279.py:2: InterpolationWarning:

The test statistic is outside of the range of p-values available in the

look-up table. The actual p-value is smaller than the p-value returned.

The KPSS (Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin) test is another test used to assess the stationarity of a time series, but it has a different null hypothesis compared to the ADF test.

KPSS Test Interpretation:

Null Hypothesis ((H_0)): The null hypothesis of the KPSS test is that the time series is stationary around a deterministic trend (i.e., it does not have a unit root).

Alternative Hypothesis ((H_1)): The alternative hypothesis is that the time series is not stationary (i.e., it has a unit root).

Given Results:

- KPSS Statistic: 1.651

- p-value: 0.01

- Critical Values:

- 10%: 0.347

- 5%: 0.463

- 2.5%: 0.574

- 1%: 0.739

Conclusion:

Reject the Null Hypothesis: The KPSS statistic (1.651) is greater than all the critical values at the 10%, 5%, 2.5%, and 1% significance levels. This, along with the low p-value (0.01), suggests that you reject the null hypothesis of stationarity.

Implication: The time series is likely non-stationary according to the KPSS test. This aligns with the ADF test results, which also indicated non-stationarity.

Overall Interpretation:

Both the ADF and KPSS tests suggest that the time series is non-stationary. This consistent result from both tests strengthens the conclusion that the series may need differencing or other transformations to achieve stationarity before further analysis or modeling.

Time Series Models

The ARIMA Family

Building blocks for forecasting:

| Model | Idea | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| AR(p) | Past values predict future | \(y_t = c + \phi_1 y_{t-1} + ... + \epsilon_t\) |

| MA(q) | Past errors predict future | \(y_t = \mu + \theta_1 \epsilon_{t-1} + ... + \epsilon_t\) |

| ARIMA(p,d,q) | AR + MA + differencing | Combines both, d = differencing order |

| SARIMA | ARIMA + seasonality | (p,d,q) × (P,D,Q,s) |

ARIMA: The Workhorse

\[ y_t = c + \underbrace{\phi_1 y_{t-1} + ... + \phi_p y_{t-p}}_{\text{AR: past values}} + \underbrace{\theta_1 \epsilon_{t-1} + ... + \theta_q \epsilon_{t-q}}_{\text{MA: past errors}} + \epsilon_t \]

ARIMA(p, d, q):

- p = AR order (how many past values?)

- d = differencing order (how many times to difference?)

- q = MA order (how many past errors?)

SARIMA: Adding Seasonality

For data with seasonal patterns, add seasonal terms:

SARIMA(p,d,q) × (P,D,Q,s)

- Lowercase (p,d,q) = short-term dynamics

- Uppercase (P,D,Q) = seasonal dynamics

- s = seasonal period (12 for monthly, 4 for quarterly)

Example: SARIMA(1,1,1)×(1,1,1,12) for monthly data with yearly seasonality

SARIMA in Practice

Let’s forecast air passengers with SARIMA(1,1,1)×(1,1,1,12):

Code

import numpy as np

from statsmodels.tsa.statespace.sarimax import SARIMAX

# Prepare data

path = os.path.join('data', 'air_passengers_1949_1960.csv')

data = pd.read_csv(path)

data['Month'] = pd.date_range(start='1949-01', periods=len(data), freq='ME')

data.set_index('Month', inplace=True)

# Log transform stabilizes growing variance

data['Log_Passengers'] = np.log(data['Number of Passengers'])# Fit SARIMA model

model = SARIMAX(data['Log_Passengers'],

order=(1, 1, 1), # (p,d,q)

seasonal_order=(1, 1, 1, 12), # (P,D,Q,s)

freq='ME')

results = model.fit()/opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.12.12/x64/lib/python3.12/site-packages/statsmodels/tsa/base/tsa_model.py:473: ValueWarning:

No frequency information was provided, so inferred frequency ME will be used.

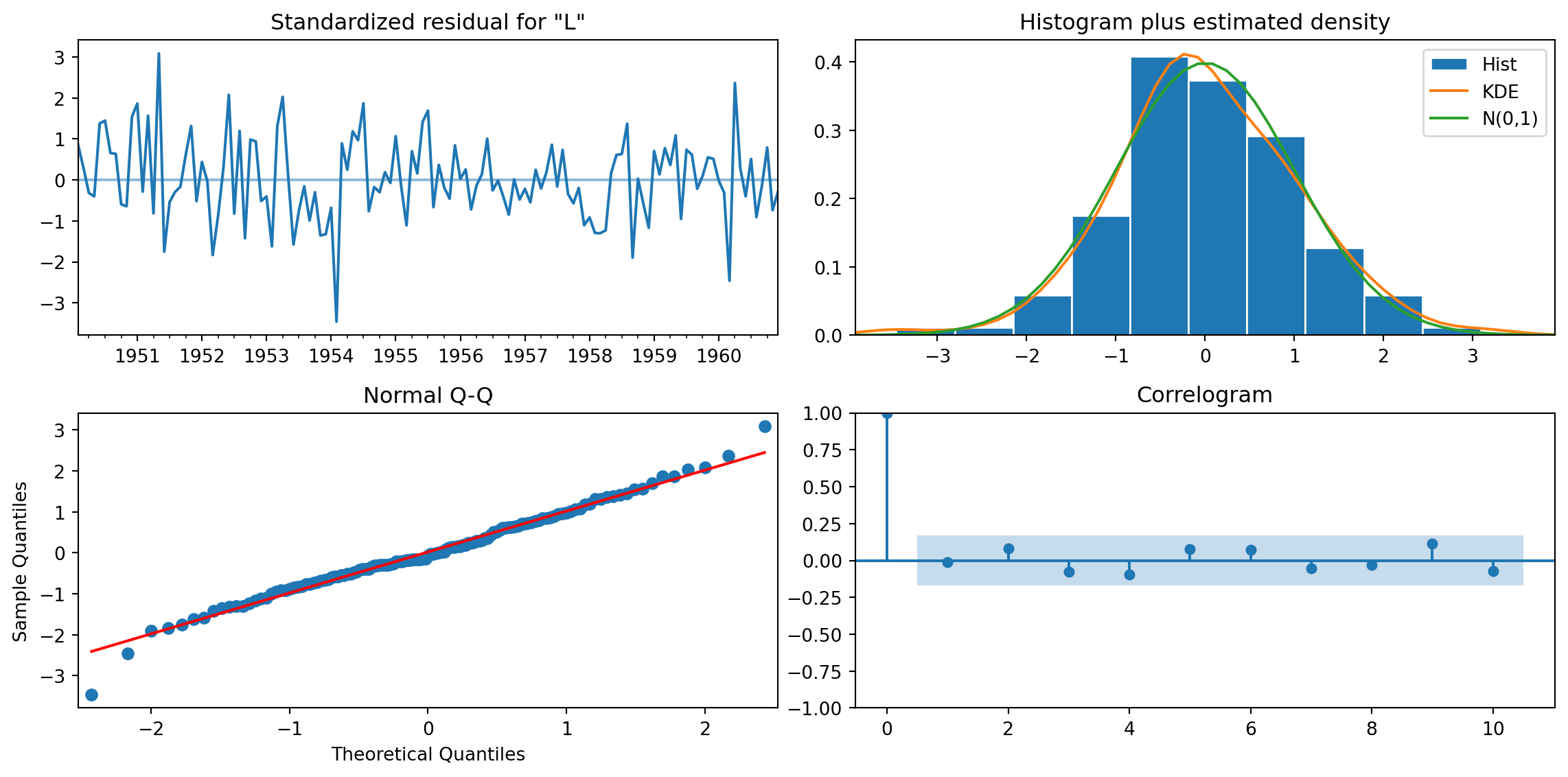

Model Diagnostics

Code

results.plot_diagnostics(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

What to check:

- Residuals: Should look like white noise (no pattern)

- Histogram: Should be roughly normal

- Q-Q plot: Points should follow the diagonal

- ACF: No significant spikes (we captured all structure)

Finally, let’s make a forecast for 2 years out.

Code

# Forecasting

forecast = results.get_forecast(steps=24)

forecast_index = pd.date_range(data.index[-1] + pd.DateOffset(months=1), periods=24, freq='ME')

forecast_values = np.exp(forecast.predicted_mean) # Convert back from log

confidence_intervals = np.exp(forecast.conf_int())

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(data['Number of Passengers'], label='Observed')

plt.plot(forecast_index, forecast_values, label='Forecast', color='red')

plt.fill_between(forecast_index, confidence_intervals.iloc[:, 0], confidence_intervals.iloc[:, 1], color='pink', alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

The light pink area shows the 95% confidence interval for the forecast.

Question: What observations do you have about the prediction?

Model Selection & Evaluation

How Do We Choose Parameters?

AIC & BIC: Balance fit vs. complexity

\[\text{AIC} = T\log\left(\frac{\text{SSE}}{T}\right) + 2k \quad \text{(lower is better)}\]

where \(k\) is the number of parameters in the model.

| Criterion | Penalizes complexity… |

|---|---|

| AIC | Moderately |

| BIC | More heavily (prefers simpler models) |

In practice: try multiple (p,d,q) combinations, pick lowest AIC/BIC.

Time Series Cross-Validation

⚠️ Can’t shuffle! Must respect temporal order.

Rolling forecast origin:

Train: [----] Test: [.]

Train: [-----] Test: [.]

Train: [------] Test: [.]Always train on past, test on future — no data leakage!

Summary

Key Takeaways

- Visualize first — trends, seasonality, autocorrelation

- Decompose — separate signal from noise (STL > classical)

- Check stationarity — transform if needed (differencing, log)

- Model — ARIMA for non-seasonal, SARIMA for seasonal

- Validate — diagnostics + time-aware cross-validation

References

- Forecasting: Principles & Practice — the definitive free textbook

- statsmodels documentation

Bibliography

Footnotes

gpt-4o, personal communication, Nov 2024↩︎