number_list = [1, 3, 5, 7]

number_list.append(8)Introduction to Python

This chapter will not be covered in lecture. It’s here to refresh the memory of those who haven’t used Python in a while.

For those that don’t know Python – but do know programming – this chapter will give you an idea of how Python is similar to, and different from, your favorite programming language.

Python is a fully object oriented programming language. It was originally created by Dutch programmer Guido van Rossum as a hobby project during his 1989 Christmas vacation. The name was inspired by Monty Python’s Flying circus.

Installing Python

There are a number of ways to install Python.

- Directly from the Python website

- Using brew install from homebrew if you are on a Mac.

- Using miniconda

- …

Python comes with a rich library of packages. You can install packages using pip or conda.

You’ll also find that you might have different version requirements for different projects that you are working on. It is best to use a virtual environment to manage your dependencies. Besides, installation and package management, conda can also be used to create virtual environments. If you don’t use conda, you can use pip to install packages.

We wrote an explanation of package management and virtual environments on this page for a previous course.

It will serve you well to become comfortable with virtual environments and package management.

How do I run code?

Python can be run interactively or via a script. For interactive versions of Python you can use Python interpreter ipython. Jupyter notebooks (.ipynb extension) run ipython in a browser. This is a great way to test out the code you are writing, demonstrate algorithms, and show visualizations. It allows for you to interact with the interpreter and fix mistakes as they happen. It has all the advantages of ipython plus interleaved documentation and graphical output.

To run Python as a script, you place all your code into a file, for example program.py and run python program.py. Scripts are used when your code has been fully debugged and tested. You want to run Python as a script when you are performing significant computations that do not require interactivity. An example of when to use a script over an interactive Jupyter notebook is if you are training a large machine learning model.

Regardless of whether you are writing scripts or notebook files, it is essential to use an Integrated Development Environment (IDE). This is a software application that helps programmers develop code efficiently. For Python, Jupyter Notebook and Jupyter Lab are both examples of interactive Python IDEs. Spyder is a Python specific IDE for developing Python scripts.

In this course, we advise using Visual Studio Code (VSCode) as your IDE. VSCode is an IDE that works for programming languages aside from Python. It has the advantage that you can develop both Python scripts (.py) and notebooks (.ipynb). In addition, there are many packages that you can install to help perform static analysis on the code you are writing. It is a very important tool to know how to use.

Functions and Methods

Function calls use standard syntax:

func(argument1, argument2)However most things you interact with in Python are objects and they have methods. A method is a function that operates on an object:

object.method(argument1, argument2)Note that the method might modify the object, or it might return a new, different object. You just have to know the method and keep track of what it does.

number_list[1, 3, 5, 7, 8]string = 'This is a string'

string.split()['This', 'is', 'a', 'string']string'This is a string'Printing

From the interactive Python environment:

print("Hello World")Hello WorldFrom a file:

print("Hello World!")Hello World!Data types

Basic data types:

- Strings

- Integers

- Floats

- Booleans

These are all objects in Python.

a = 7

type(a)intb = 3

type(b)intc = 3.2

type(c)floatd = True

type(d)boolPython doesn’t require explicitly declared variable types like C and other languages. Python is dynamically typed.

myVar = 'I am a string'

print(myVar)

myVar = 2.3

print(myVar)I am a string

2.3Strings

String manipulation will be very important for many of the tasks we will do. Here are some important string operations.

A string uses either single quotes or double quotes. Pick one option and be consistent.

'This is a string''This is a string'"This is also a string"'This is also a string'The ‘+’ operator concatenates strings.

a = "Hello"

b = " World"

a + b'Hello World'Portions of strings are manipulated using indexing (which Python calls ‘slicing’).

a = "World"

a[0]'W'a[-1]'d'"World"[0:4]'Worl'a[::-1]'dlroW'Some important string functions:

a = "Hello World"

"-".join(a)'H-e-l-l-o- -W-o-r-l-d'a.startswith("Wo")Falsea.endswith("rld")Truea.replace("o", "0").replace("d", "[)").replace("l", "1")'He110 W0r1[)'a.split()['Hello', 'World']a.split('o')['Hell', ' W', 'rld']Strings are an example of an immutable data type. Once you instantiate a string you cannot change any characters in it’s set.

string = "string"

string[-1] = "y" # This will generate and error as we attempt to modify the string--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[25], line 2 1 string = "string" ----> 2 string[-1] = "y" # This will generate and error as we attempt to modify the string TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

To create a string with embedded objects use the .format() method:

course_name = 'DS701'

enrollment = 90

percent_full = 100.0

'The course {} has an enrollment of {} and is {} percent full.'.format(

course_name, enrollment, percent_full)'The course DS701 has an enrollment of 90 and is 100.0 percent full.'A special formatting called an f-string allows you to print out variables very conveniently:

f'The course {course_name} has an enrollment of {enrollment} and is {percent_full} percent full.''The course DS701 has an enrollment of 90 and is 100.0 percent full.'Code Structure

Python uses indents and whitespace to group statements together. To write a short loop in C, you might use:

for (i = 0, i < 5, i++){

printf("Hi! \n");

}Python does not use curly braces like C, so the same program as above is written in Python as follows:

for i in range(5):

print("Hi")Hi

Hi

Hi

Hi

HiIf you have nested for-loops, there is a further indent for the inner loop.

for i in range(3):

for j in range(3):

print(i, j)

print("This statement is within the i-loop, but not the j-loop")0 0

0 1

0 2

This statement is within the i-loop, but not the j-loop

1 0

1 1

1 2

This statement is within the i-loop, but not the j-loop

2 0

2 1

2 2

This statement is within the i-loop, but not the j-loopFile I/O

open() and close() are used to access files. However if you use the with statement the file close is automatically done for you.

You should use with.

with open("example.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("Hello World! \n")

f.write("How are you? \n")

f.write("I'm fine. OK.\n")Reading from a file:

with open("example.txt", "r") as f:

data = f.readlines()

for line in data:

words = line.split()

print(words)['Hello', 'World!']

['How', 'are', 'you?']

["I'm", 'fine.', 'OK.']Here is an example of counting the number of lines and words in a file:

lines = 0

words = 0

the_file = "example.txt"

with open(the_file, 'r') as f:

for line in f:

lines += 1

words += len(line.split())

print(f"There are {lines} lines and {words} words in the {the_file} file.")There are 3 lines and 8 words in the example.txt file.Lists, Tuples, Sets and Dictionaries

Number and strings alone are not enough! We need data types that can hold multiple values.

Lists

A list is a collection of data items, which can be of differing types.

Here is an empty list:

groceries = []A list is mutable, meaning that it can be altered.

Adding to the list:

groceries.append("oranges")

groceries.append("meat")

groceries.append("asparagus")

groceries['oranges', 'meat', 'asparagus']Accessing list items by index:

groceries[0]'oranges'groceries[2]'asparagus'len(groceries)3Sort the items in the list:

groceries.sort()

groceries['asparagus', 'meat', 'oranges']Remove an item from a list:

groceries.remove('asparagus')

groceries['meat', 'oranges']Because lists are mutable, you can arbitrarily modify them.

groceries[0] = 'peanut butter'

groceries['peanut butter', 'oranges']List Comprehensions

A list comprehension makes a new list from an old list.

It is incredibly useful and you definitely need to know how to use it.

groceries = ['asparagus', 'meat', 'oranges']

veggie = [x for x in groceries if x != "meat"]

veggie['asparagus', 'oranges']This is the same as:

newlist = []

for x in groceries:

if x != 'meat':

newlist.append(x)

newlist['asparagus', 'oranges']Recall the mathematical notation:

\[L_1 = \left\{x^2 : x \in \{0\ldots 9\}\right\}\]

\[L_2 = \left\{2^0, 2^1, 2^2, 2^3,\ldots, 2^{12}\right\}\]

\[M = \left\{x \mid x \in L_1 \text{ and } x \text{ is even}\right\}\]

L1 = [x**2 for x in range(10)]

L2 = [2**i for i in range(13)]

print(f'L1 is {L1}')

print(f'L2 is {L2}')L1 is [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

L2 is [1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096]M = [x for x in L1 if x % 2 == 0]

print('M is {}'.format(M))M is [0, 4, 16, 36, 64]A “Sieve of Eratosthenes” in list comprehensions.

Basic idea: generate composite numbers, remove them from the set of all numbers, and what is left are the prime nnumbers.

limit = 50

composites = [n for n in range(4, limit+1) if any(n % i == 0 for i in range(2, int(n**0.5)+1))]primes = [x for x in range(1, 50) if x not in composites]

print(primes)[1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47]Notice how much more concise and clear the list comprehension is. It’s more efficient too.

Sets

A set is a collecton of items that cannot contain duplicates.

Sets handle operations like sets in mathematics.

numbers = range(10)

numbers = set(numbers)

evens = {0, 2, 4, 6, 8}

odds = numbers - evens

odds{1, 3, 5, 7, 9}Sets also support the use of union (|), and intersection (&)

Dictionaries

A dictionary is a map of keys to values.

Keys must be unique.

simple_dict = {}

simple_dict['DS701'] = 'tools for data science'

simple_dict['DS701']'tools for data science'Creating an already-initialized dictionary. Note the use of curly braces.

classes = {

'DS701': 'tools for data science',

'DS542': 'deep learning for data science'

}Check if item is in dictionary

'DS680' in classesFalseAdd new item

classes['DS680'] = 'data society and ethics'

classes['DS680']'data society and ethics'Get just the keys

classes.keys()dict_keys(['DS701', 'DS542', 'DS680'])Get just the values

classes.values()dict_values(['tools for data science', 'deep learning for data science', 'data society and ethics'])Get the items in the dictionary

classes.items()dict_items([('DS701', 'tools for data science'), ('DS542', 'deep learning for data science'), ('DS680', 'data society and ethics')])Get dictionary pairs another way

for key, value in classes.items():

print(key, value)DS701 tools for data science

DS542 deep learning for data science

DS680 data society and ethicsDictionaries can be combined to make complex (and very useful) data structures.

Here is a list within a dictionary within a dictionary.

professors = {

"prof1": {

"name": "Thomas Gardos",

"interests": ["large language models", "deep learning", "machine learning"]

},

"prof2": {

"name": "Mark Crovella",

"interests": ["computer networks", "data mining", "biological networks"]

},

"prof3": {

"name": "Scott Ladenheim",

"interests": ["numerical linear algebra", "deep learning", "quantum machine learning"]

}

}for prof in professors:

print('{} is interested in {}.'.format(

professors[prof]["name"],

professors[prof]["interests"][0]))Thomas Gardos is interested in large language models.

Mark Crovella is interested in computer networks.

Scott Ladenheim is interested in numerical linear algebra.Tuples

Tuples are an immutable type. Like strings, once you create them, you cannot change them.

Because they are immutabile you can use them as keys in dictionaries.

However, they are similar to lists in that they are a collection of data and that data can be of differing types.

Here is a tuple version of our grocery list.

groceries = ('orange', 'meat', 'asparagus', 2.5, True)

groceries('orange', 'meat', 'asparagus', 2.5, True)groceries[2]'asparagus'What will happen here?

groceries[2] = 'milk'--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[60], line 1 ----> 1 groceries[2] = 'milk' TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

Iterators and Generators

We can loop over the elements of a list using for

for i in range(4):

print(i)0

1

2

3When we use for for dictionaries it loops over the keys of the dictionary

for k in {'thomas': 'gardos', 'scott': 'ladenheim'}:

print(k)thomas

scottWhen we use for for strings it loops over the letters of the string:

for l in 'python is magic':

print(l)p

y

t

h

o

n

i

s

m

a

g

i

cWhat do these cases all have in common? All of them are iterable objects.

list({'thomas': 'gardos', 'scott': 'ladenheim'})['thomas', 'scott']list('python is magic')['p', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n', ' ', 'i', 's', ' ', 'm', 'a', 'g', 'i', 'c']'-'.join('thomas')'t-h-o-m-a-s''-'.join(['a', 'b', 'c'])'a-b-c'Defining Functions

def displayperson(name,age):

print("My name is {} and I am {} years old.".format(name,age))

return

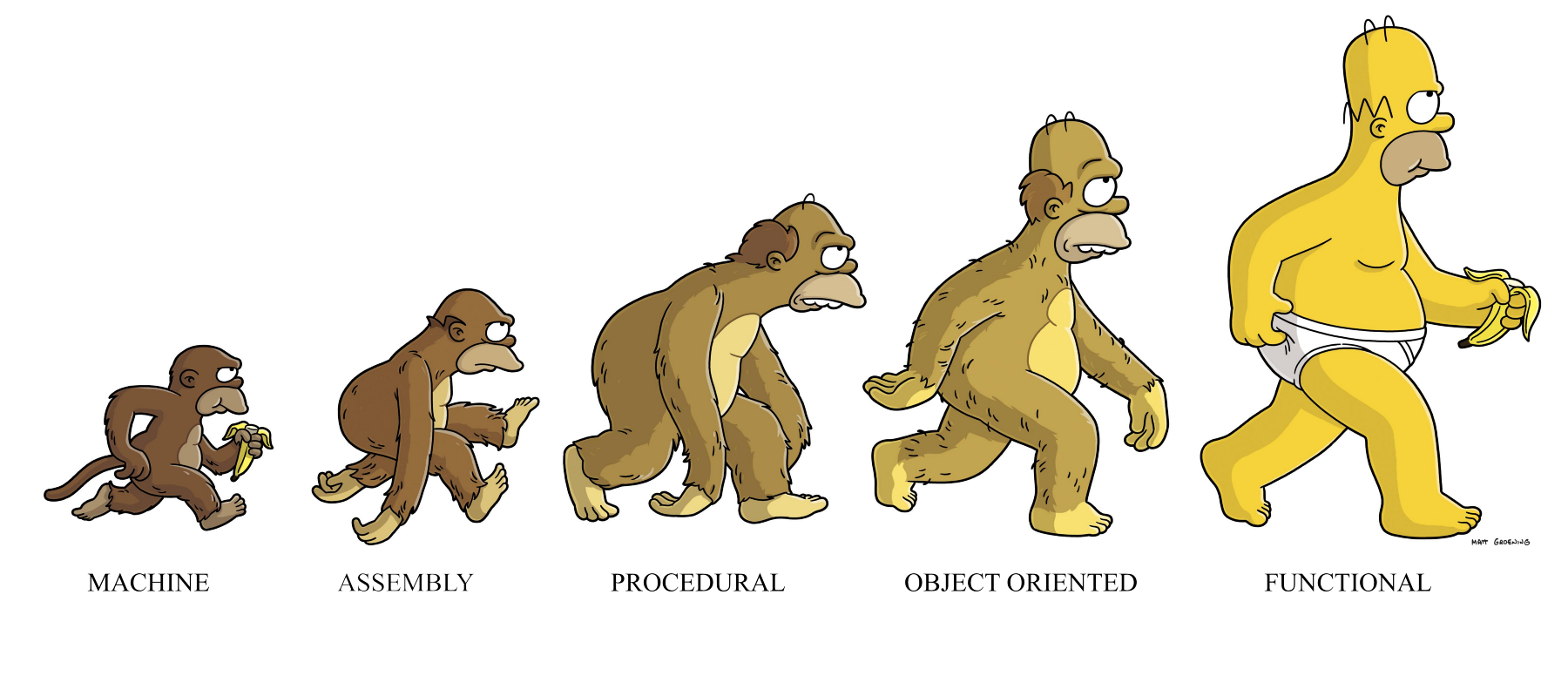

displayperson("Larry", "40")My name is Larry and I am 40 years old.Functional Programming

Functional programming is particularly valuable and common when working with data.

We’ll see more sophisticated examples of this sort of programming later.

Lambda functions

Python supports the creation of anonymous functions (i.e. functions that are not bound to a name) at runtime, using a construct called lambda.

def f(x):

return x**2

f(8)64g = lambda x: x**2

g(8)64(lambda x: x**2)(8)64The above pieces of code are all equivalent! Note that there is no return statement in the lambda function. Instead there is just a single expression, which defines what the function returns.

A lambda function can take multiple arguments. However it has to get all its work done in a single line of code!

f = lambda x, y : x + y

f(2,3)5A lambda function does not need to be assigned to variable, but it can be used within the code wherever a function is expected.

Here is an example of ‘currying’: a function that returns a new function, with some of the original arguments bound.

def multiply (n):

return lambda x: x*n

f = multiply(2)

g = multiply(6)

f<function __main__.multiply.<locals>.<lambda>(x)>f(10)20g(10)60multiply(3)(30)90Map

Our first example of functional programming will be the map operator:

r = map(func, s)

func is a function and s is a sequence (e.g., a list).

map() returns an object that will apply function func to each of the elements of s.

def dollar2euro(x):

return 0.89*x

def euro2dollar(x):

return 1.12*x

amounts= (100, 200, 300, 400)

dollars = map(dollar2euro, amounts)

list(dollars)[89.0, 178.0, 267.0, 356.0]amounts= (100, 200, 300, 400)

euros = map(euro2dollar, amounts)

list(euros)[112.00000000000001,

224.00000000000003,

336.00000000000006,

448.00000000000006]list(map(lambda x: 0.89*x, amounts))[89.0, 178.0, 267.0, 356.0]map can also be applied to more than one list as long as they are of the same size and type

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

b = [10, 20 , 30, 40, 50]

l1 = map(lambda x,y: x+y, a, b)

list(l1)[11, 22, 33, 44, 55]Filter

The next functional operator is filter.

filter(function, list) returns a new list containing all the elements of list for which function() evaluates to True.

nums = [i for i in range(100)]

even = filter(lambda x: x%2==0 and x!=0, nums)

print(even)

list(even)<filter object at 0x115134580>[2,

4,

6,

8,

10,

12,

14,

16,

18,

20,

22,

24,

26,

28,

30,

32,

34,

36,

38,

40,

42,

44,

46,

48,

50,

52,

54,

56,

58,

60,

62,

64,

66,

68,

70,

72,

74,

76,

78,

80,

82,

84,

86,

88,

90,

92,

94,

96,

98]Libraries

Python is a high-level open-source language. But the Python world is inhabited by many packages or libraries that provide useful things like array operations, plotting functions, and much more.

We can (and we will) import many different libraries of functions to expand the capabilities of Python in our programs.

import random

myList = [2, 109, False, 10, "data", 482, "mining"]

random.choice(myList)10from random import shuffle

x = list(range(10))

shuffle(x)

x[6, 1, 4, 8, 9, 2, 3, 0, 7, 5]APIs

For example, there are libraries that make it easy to interact with RESTful APIs.

A RESTful API is a service available on the Internet that uses the HTTP protocol for access.

import requests

width = '200'

height = '300'

response = requests.get('http://loremflickr.com/' + width + '/' + height)

print(response)

with open('img.jpg', 'wb') as f:

f.write(response.content)<Response [500]>from IPython.display import Image

Image(filename="img.jpg")

Resources

Here are some handy Python resources.

- The official Python webpage.

- Wes McKinney’s Python for Data Anaylsis, 3E.

For a quick hands-on refresher of Python you can always attend the (free) Python tutorials offered by Boston University’s Research Computing Services (RCS). The tutorial schedule is at this link. In addition to Python, RCS offers tutorials on a variety of relevant topics in this course, such as machine learning, natural language processing, and using Pytorch.